In the winter of 2009, Stephanie Davis had developed a routine. Twice a week, she went to the hospital with her 3-year-old son, Yamil. She was pregnant, and Yamil loved to tag along. He would feel his baby sister move, and he’d listen to her heart beating.

But at one particular doctor’s appointment in February, something was off.

It was Yamil who said it out loud first, even before the doctor.

“Hey, where’s her heartbeat?” Stephanie remembers her son asking.

The doctor ran out of the room to get a second opinion from a nurse, but Yamil was right.

The baby, McKayla, was dead.

At 36 weeks, Stephanie had carried McKayla nearly to full-term. She was forced to spend the next day, Feb. 25, living life as normal, all the while aware that she was carrying a child who had already passed away.

“I blacked out,” Stephanie said. “I don’t remember very much. I remember laying around, I couldn’t do anything.”

Then, on Feb. 26, the doctors induced labor. Stephanie asked the doctors to give her a cesarean section, but they said no. Stephanie had to give birth to McKayla as if she were a living child. She held her dead baby for only a minute before the nurses took her away.

“That’s one of those things that eats me alive to this day. That I didn’t get a chance to hold her. I didn’t even get a chance to bring her in close,” Stephanie said.

Stephanie was a 24-year-old U.S. Marine at the time. She was living at Laurel Bay and working on Parris Island as a quality insurance inspector. She and her ex-husband already had two children: Yamil and Jade, who was nearly 2. Stephanie was healthy, physically fit, and had no complications with either of her older children. The doctors were at a total loss as to why McKayla had passed away while still in the womb.

Stephanie said she does not directly blame the Marine Corps for what happened.

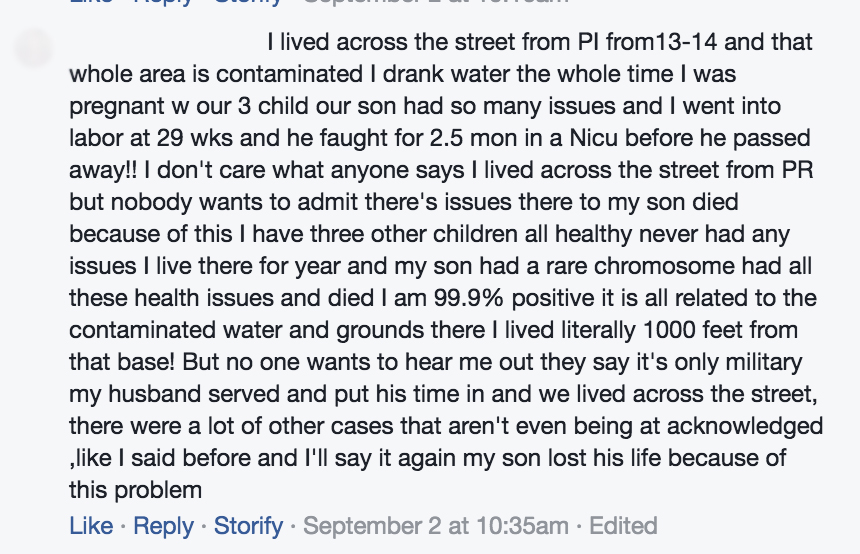

But Stephanie wasn’t the only parent from Laurel Bay with pregnancy and fertility problems. In a Facebook group specifically created for parents concerned about whether contamination at Laurel Bay affected their children’s health, several parents spoke about miscarriages and fertility issues while living at Laurel Bay and after moving away, too.

(Note: The identities of the parents below have been withheld to protect their privacy.)

“I’m wondering about infertility issues that I experienced,” wrote one mother. “I had 3 miscarriages in between my 13 year old and 6 year old. All while living on LB (Laurel Bay).”

“I had 2 miscarriages while living in Laurel Bay,” wrote another. “This is so disappointing. I really dont (sic) understand why all military housing hasn’t been on top of this.”

At least five different women on the Facebook page mentioned miscarriages; five noted developing cysts on their ovaries after moving to Laurel Bay; two mentioned “fertility issues” in general; and one said she’d developed cholestasis, a liver condition that usually occurs late in the pregnancy that could cause complications for the infant.

In the U.S., miscarriages are far more common than stillbirths. About 17 percent of pregnancies ended in miscarriage in 2010, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and 1 percent end in a stillbirth. This is because women are more likely to lose their child early on in their pregnancies — specifically, in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy, when the loss of a fetus is considered a miscarriage, than after 20 weeks, when it’s considered a stillbirth.

To further complicate matters, doctors often don’t know why women miscarry or deliver stillborn children.

No scientist, doctor, or researcher has pursued a study to learn whether contamination at Laurel Bay could have caused fertility problems. Therefore, it’s impossible to say with any certainty whether there’s a causal connection.

However, at least one of the contaminants at Laurel Bay has been linked to fertility issues. That contaminant is chlordane, a pesticide used in Laurel Bay well into the 1990s to kill termites, despite the fact that the federal government forbade its usage in 1988.

Perhaps most disconcerting, chlordane was still found in the ground at Laurel Bay long after it was banned and years after it was no longer used.

In 1979, the Committee of Toxicology with the National Academy of Sciences concluded it “could not determine a level of exposure to chlordane below which there would be no biologic effect under conditions of prolonged exposure of families in military housing.”

In a public health statement published by the CDC in 1994, researchers concluded:

“It is not known whether chlordane will cause reproductive or birth defects in humans. Studies of workers who made or used chlordane do not link exposure to the chemical with birth defects, but there are not enough studies in humans to know for sure. There is some evidence that animals exposed before birth or while nursing develop behavioral effects while growing up.”

But previously, studies showed that chlordane could lead to infertility in rats. In 1987, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency released a document summarizing the research about various pesticides. Chlordane, as researchers found out in 1971, reduced fertility in rats by 50 percent.

Although the effects of chlordane on humans are not clear, the federal government ruled that the possible consequences were risky enough that chlordane should be banned.

For Stephanie, the difficulties were not over after McKayla’s death and cremation. She developed a painful ovarian cyst and suffered three miscarriages. She grew depressed and began to see a therapist. But even that couldn’t save her first marriage — she and her husband divorced in 2012 because of an irreconcilable wedge driven between them by depression and disagreements on whether to have more children.

And then there were the nightmares.

For eight years after McKayla’s death, Stephanie had a recurring dream, one that frightened her. In this dream, she always gave birth to a child — sometimes in a car, sometimes out in public — except that in this scenario, Stephanie didn’t realize she was pregnant. She would give birth, her mind tricking her into thinking that the physical pain was real, and she would pick the newborn up. The baby would pause for a moment, and then it would cry. A dream of what could have been.

“I don’t necessarily expect everybody to understand that, why that’s a nightmare for me,” Stephanie said. “But it’s a nightmare because I gave birth to a child that didn’t even move, that didn’t cry.”

The nightmares finally stopped when her third child, Caleb, was born in April of this year.

And things continue to look up. She remarried in 2014, and Caleb, Yamil and Jade are happy and healthy. Stephanie still works for the Marine Corps, and she says she is happy with her job.

But still today, even as Stephanie cares for her children, and even after her nightmares have passed, she thinks about McKayla every day.

“I questioned myself many times,” Stephanie said. “Did I fall? Did I do this, that or whatever? And I didn’t! So that’s just the mystery — nobody could explain to me what had happened to my child.”

Stephanie believes that one day, she’ll find answers. Perhaps, she hopes, with those answers, she might finally find closure, too.

Kasia Kovacs: 843-706-8139, @kasiakovacs