The trouble started with a giant dirt hole that appeared in Michelle Conner’s front yard.

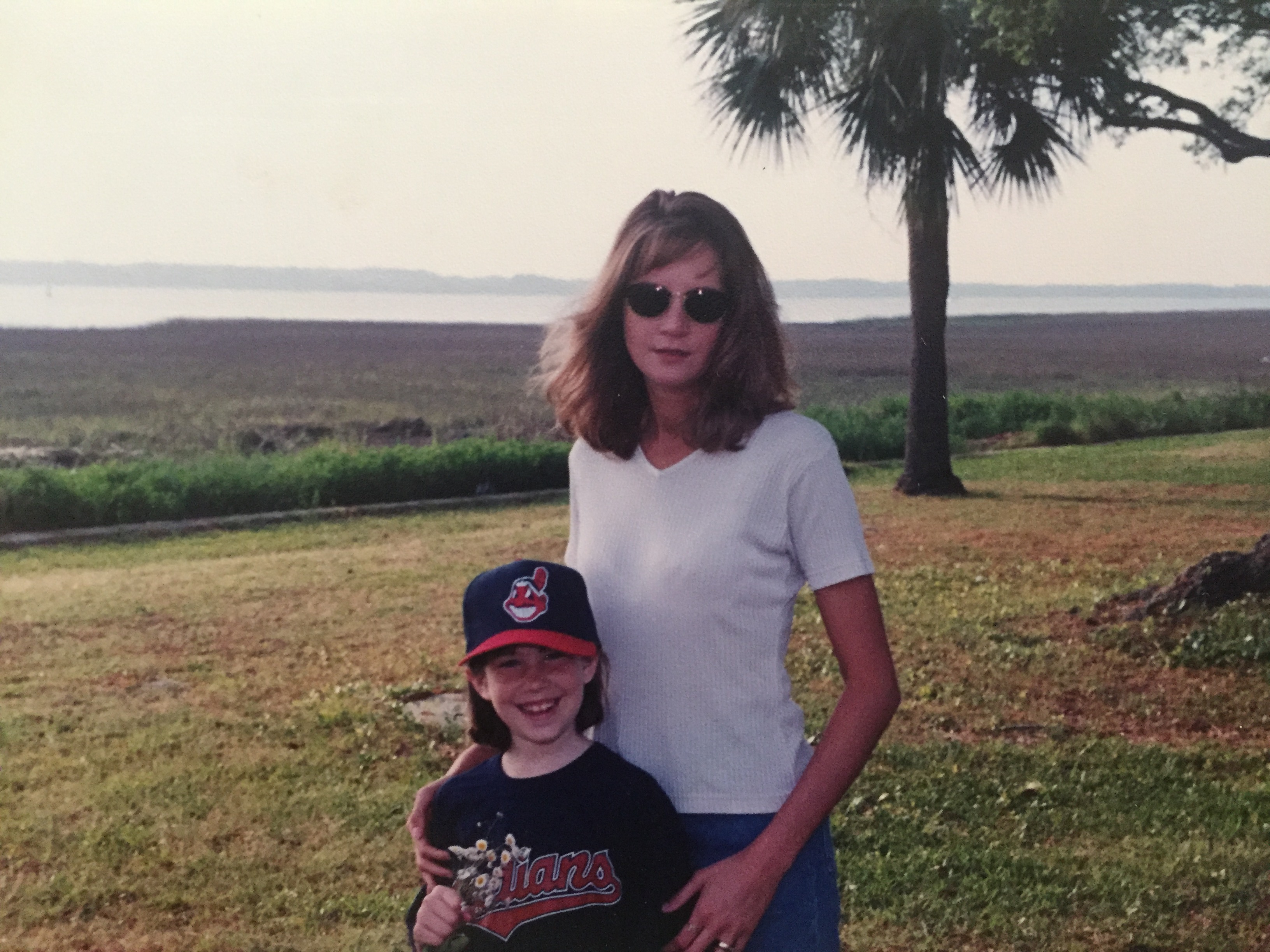

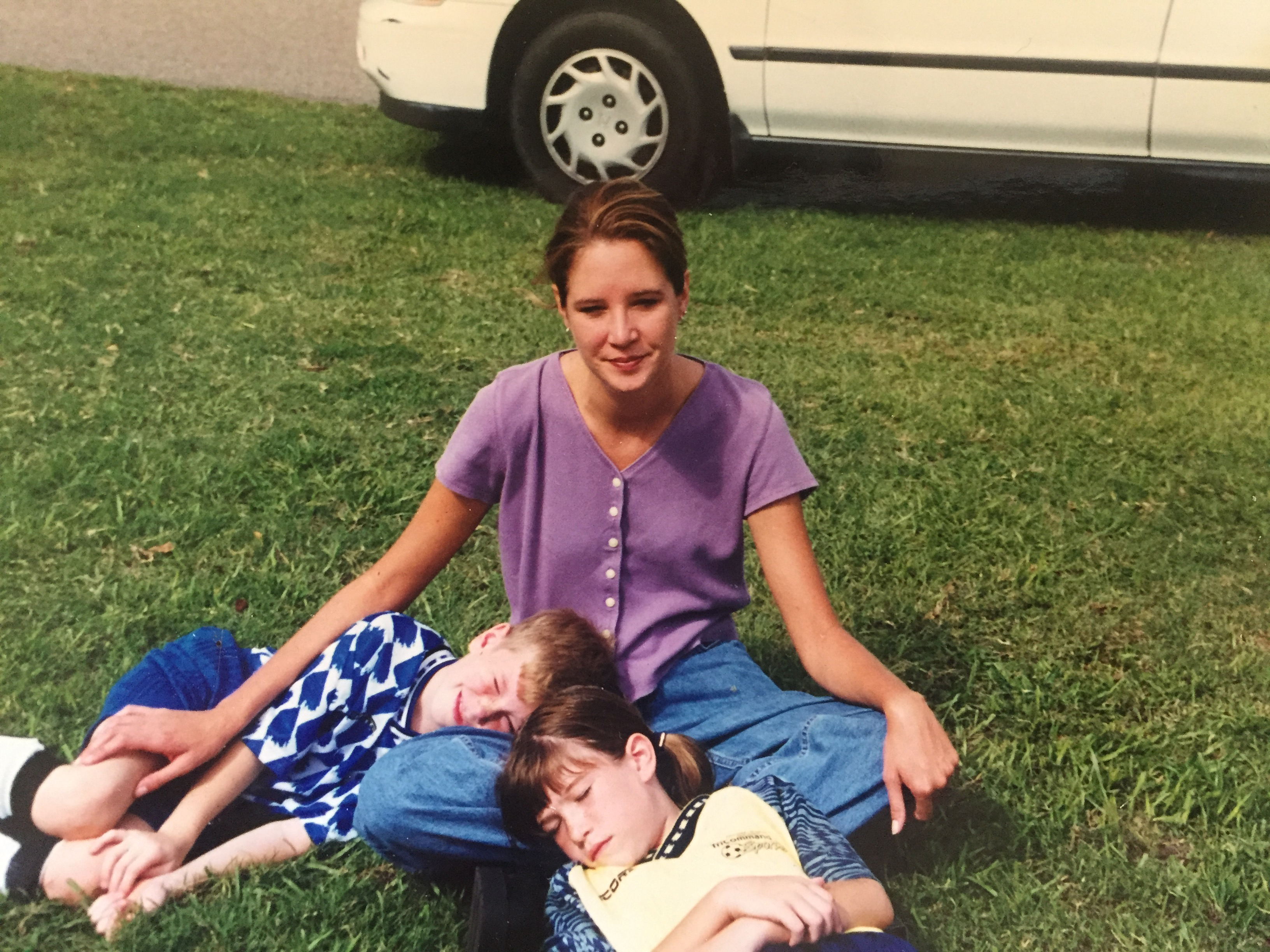

That’s how Conner remembers it, anyway. It was 1999, and she was 9 and living in the Laurel Bay Marine housing community near Beaufort. All she knew was this: One day Conner could ride her bike in the front yard, and the next day she couldn’t.

Her mother forbid her from playing in or around the hole, which was about as wide as a sidewalk and stretched across their entire yard. To young Conner, then a freckled girl with a toothy grin who spent all her time playing outside, staying away from the giant dirt hole seemed an impossible task. That hole was a gift — the perfect hiding spot for hide-and-seek and a perfect trench for capture the flag.

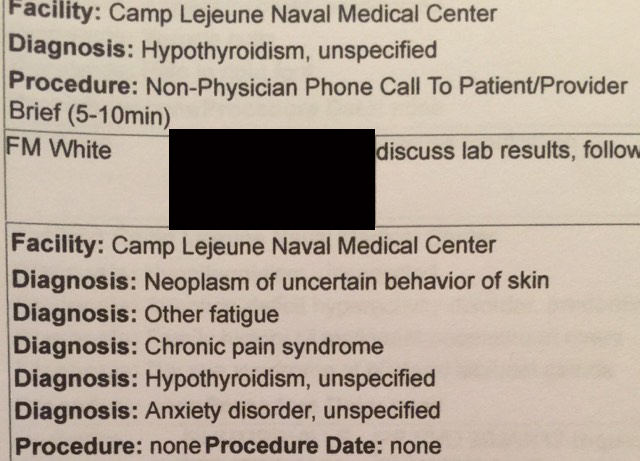

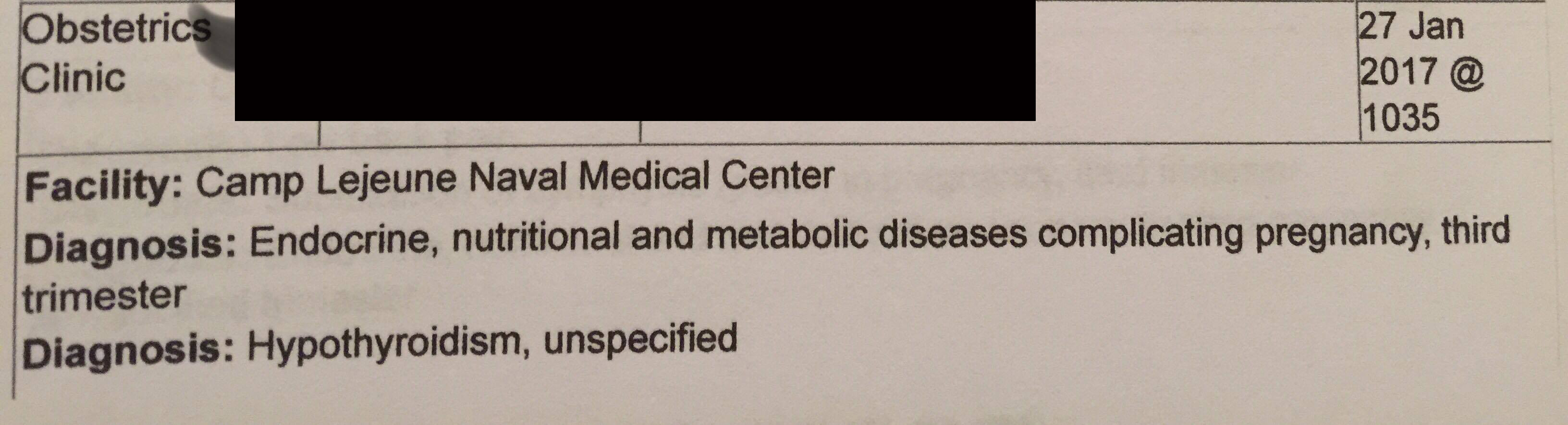

After Conner’s family moved away from Laurel Bay at the end of the year, her health took a nosedive. By the time was 21, she was diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome, arthritis, Hashimoto’s disease, Grave’s disease, supraventricular tachycardia and thyroiditis, she says.

Then, in January, she saw a video on Facebook. In the video, a Marine wife named Amanda Whatley spoke about her child Katie, who was diagnosed with leukemia. Whatley and her family questioned whether Katie’s cancer had something to do with heating oil storage tanks buried under the ground of Laurel Bay. Heating oil that had leaked — potentially for decades — was suspected of contaminating the ground with benzene, a known carcinogen, and naphthalene, a possible carcinogen.

Conner’s mind raced. Could that dirt hole in the ground be connected to the oil tanks? And could the contamination from those tanks have anything to do with her illnesses? She had lived on Laurel Bay for the majority of her elementary school years. All that time living in that house on Laurel Bay, all those years playing outside — could she have been exposed as a child?

For Conner and countless other former and current Laurel Bay residents, Whatley’s video started a flurry of potential connecting of dots; of what would become months of worry, fright, anger and confusion. But the video also prompted a sense of community, as families feeling betrayed by the military turned to each other for support and information.

Lately, Conner says she’s grown used to losing consciousness two or three times a week. And in November, six days after she turned 27, she found out she had lupus. Her immune system had essentially been attacking itself, Conner said.

For the majority of her life, Conner’s illnesses confounded her.

“Before, I was so sick and nobody listened to me,” Conner says, exasperated by the memory. “Why (couldn’t) anyone see how sick I was?”

But online, at least, she had found a community.

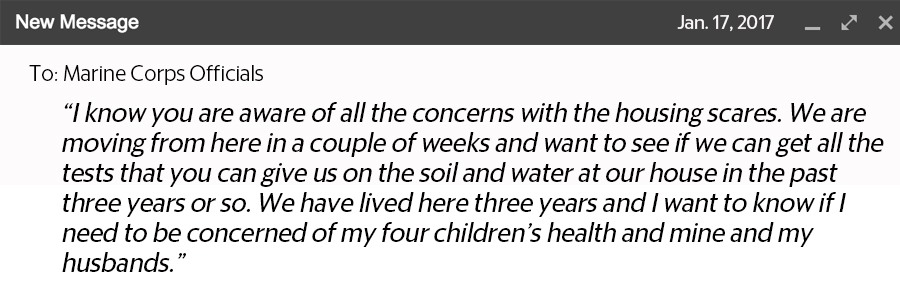

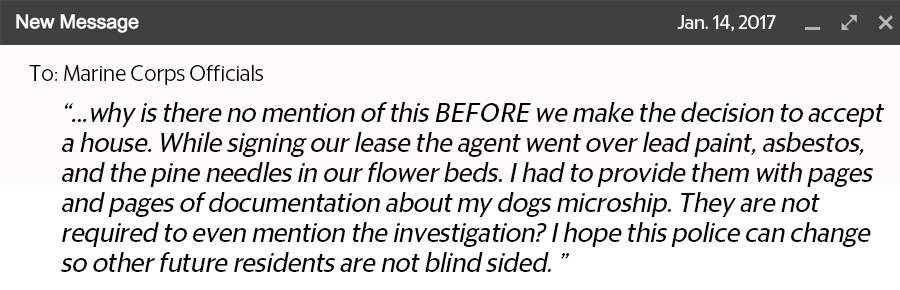

Conner was one of many former and current Laurel Bay residents who wanted answers from the Marine Corps after Whatley's YouTube video went viral. A flood of emails — 192 pages of which were obtained by The Island Packet and The Beaufort Gazette through a federal Freedom of Information Act request — inundated MCAS officials:

“I know you are aware of all the concerns with the housing scares…,” wrote one resident in an email. “We have lived here three years and I want to know if I need to be concerned (for) my four children’s health and mine and my husbands (sic).”

Another blasted officials for failing to inform residents: “Like most residents, I was blind sided (sic) by the video and all of the following information about possible contamination. I guess my question is why is there no mention of this BEFORE we make the decision to accept a house.”

Some residents requested an immediate home reassignment. Others asked for follow-up testing to their homes. One mother asked the military to move her family off base into a hotel — no less than two stars.

For the most part, they received a boilerplate response: Be patient. The Marine Corps had begun an environmental health study in 2015, and officials assured families their findings would be published soon.

Officials held two town hall meetings a week after Whatley’s video caught fire to try to quell worries. But the microphone at the meetings only amplified the resentment in residents’ voices as they asked questions.

“There is no reliable data, right now, at all to suggest that there is a pathway (for exposure),” Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort commanding officer P.D. Buck said in response to one question from a resident.

“But that’s just what you’re saying,” the resident retorted. “We haven’t had any actual evidence. Correct?”

“That’s what the study is looking at,” Buck said.

The health study wouldn’t be published until the end of September, several months after it was promised. Conducted by the Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center, it concluded a connection between the contamination and the children’s cancer was unlikely. Researchers said they did not find enough pediatric cancer cases to constitute a cancer cluster among children, and epidemiologists did not find complete exposure pathways.

The study didn’t do much to calm many residents.

“I call bullshit,” commented one former resident on an Island Packet and Beaufort Gazette article about the health study.

With that feeling of helplessness and anger, many residents were left wondering, who could they trust?

The answer, as it turns out, was each other.

Conner’s childhood friend invited her to a closed Facebook group for concerned military families who had lived in Beaufort. The group was originally started in 2015 by a few parents who were worried about their children’s health at Laurel Bay. After Whatley posted her video, over 2,500 members joined. Many of them were former residents like Conner, curious whether the contamination had anything to do with their or their friends’ illnesses.

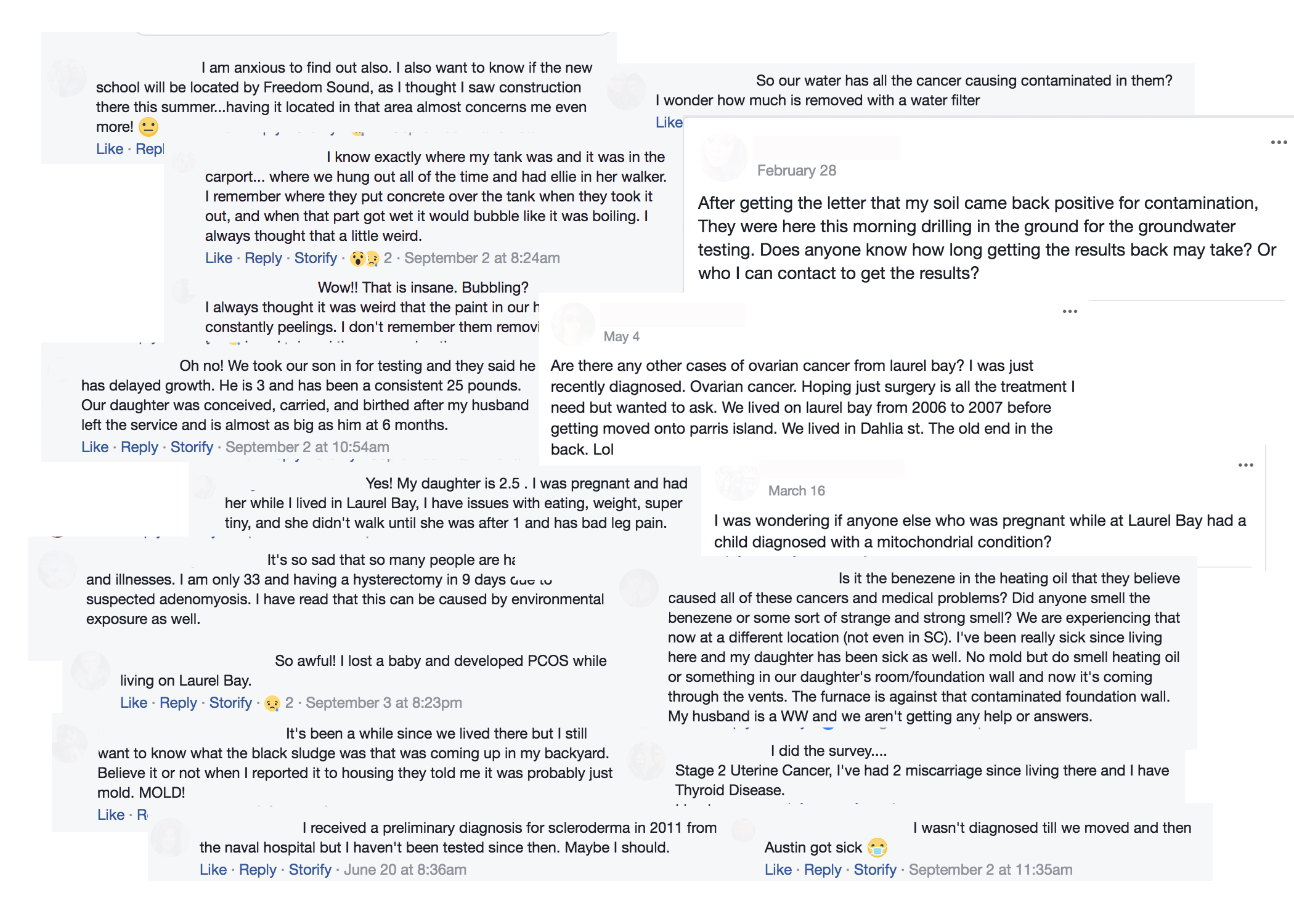

They shared photos of their children with burning red faces. They told stories of their children with rare conditions, chromosome abnormalities, dwarfism, developmental delays, brain cancer, leukemia and asthma. Adults spoke about their problems with infertility, migraines and fatigue.

They asked each other questions that remained unanswered from the Marine Corps — how to ask their doctors for the correct tests, for instance:

“I took (my kids) to be tested for cancer and leukemia and the doc said there is no specific test,” one mother wrote.

“My husband wants full blood work (for my daughter) done. I’m wanting to know what I should be asking for?” wrote another.

“My daughter seems healthy all around.. but all of this is very concerning... should I get her blood tested to be on the safe side?” wrote a third.

It was a place where they could vent: “GET OUT. Seriously. Put your 30 days in and get out,” wrote one resident. “It may seem silly that I’m posting this, but I am outraged, and I think we all have earned the right to be.”

They shared news articles, critiquing the news reports that dismissed their worries.

And social media became a place where they could commiserate and compare notes. Residents shared strange observations they’d noticed over the years, much like Conner’s experience with that giant dirt hole.

“It’s been awhile since we lived there but I still want to know what the black sludge was that was coming up in my backyard,” one woman wrote. “Believe it or not when I reported it to housing they told me it was probably just mold. MOLD!”

“We had black gunk come up through our floors and they said it was glue from the floors getting too hot…” another resident responded.

Another woman spoke of “the smell of heating oil throughout” her home — “a sweet strange oily smell,” she wrote. “I can always smell it.” Others, impatient for researchers to test the air quality in their homes, said they bought their own vapor intrusion testing kits.

When the Marine Corps concluded in September that residents were not exposed to the contamination, members of the Facebook group grew angry. They grew gardens and ate the vegetables, they said. What about their kids who played in the dirt? What about small children who may have unknowingly chewed on lead paint chips?

Neither Whatley nor Melany Lualhati Martin Stawnyczyj, an administrator in the Facebook group, would speak to the Packet or Gazette. An attorney for Whatley and other former residents cited an ongoing lawsuit against Laurel Bay's private management company.

But in January, Stawnyczyj wrote, “I am thankful to God that our platform has finally begun to go beyond Facebook and word of mouth.”

Experts warn against the dangers of self-diagnosis. Every disease — including cancer — could have multiple causes, some of which have nothing to do with environmental exposure, and those who feel uneasy should visit a doctor to check their concerns, they say.

Marine officials have also warned residents to remain skeptical about what they read on Facebook and other social media.

“A lack of information about either the facts or the command’s actions can cause anxiety. I have tried to avoid providing incomplete or inaccurate information; which could have caused speculation,” commanding officer Buck wrote in a letter from January.

But some residents believe that after the Marine Corps failed to notify all residents about the contaminated oil tanks, the information they received from officials was incomplete in the first place.

Conner says connecting with other Marine spouses on social media has allowed her to feel as if she’s not simply an anomaly, nor a hypochondriac. It gave her the confidence to open up to her doctors about her experiences on Laurel Bay.

And besides, Conner and others say, the point of social media is not to self-diagnose. It’s a way to empower one another, a medium allowing military families to give each other comfort that seems to be impossible to find elsewhere — a way to take care of their own.

Kasia Kovacs: 843-706-8139, @kasiakovacs

Next Story: Hazardous waste sites near Laurel Bay