For years, some parents living on Laurel Bay quietly wondered why their children were diagnosed with cancer.

In January, Amanda Whatley, the wife of a Marine and a former Laurel Bay resident, posted a YouTube video questioning if her daughter’s leukemia diagnosis stemmed from their stay on base from 2007 to 2010.

In an update posted with the video, Whatley said the number of known cases of Laurel Bay children diagnosed with cancer had grown to 13 and that she had heard from 20 adults who had been stationed in Beaufort and later diagnosed with cancer.

Suddenly, it seemed like there might be an answer to the cancer question: the underground heating oil tanks buried beneath the yards of their Laurel Bay homes.

But the Marine Corps’ pediatric cancer study released in October found it “unlikely” — meaning there was “insufficient evidence” — that an environmental or occupational exposure was associated with the types of cancer identified among children of residents and former residents.

In addition, the Corps’ study of soil and groundwater found no likely exposure pathway for contamination to reach residents of Laurel Bay.

Authors of the study confirmed 15 children’s cancer cases — one case shy of what they said was the National Cancer Institute’s minimum of 16 cases to calculate a valid ratio.

“In my experience, we’ve never been able to get enough cases to actually study,” said Dr. Chris Rennix, head of the Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Epidata Center, which conducted Laurel Bay’s study.

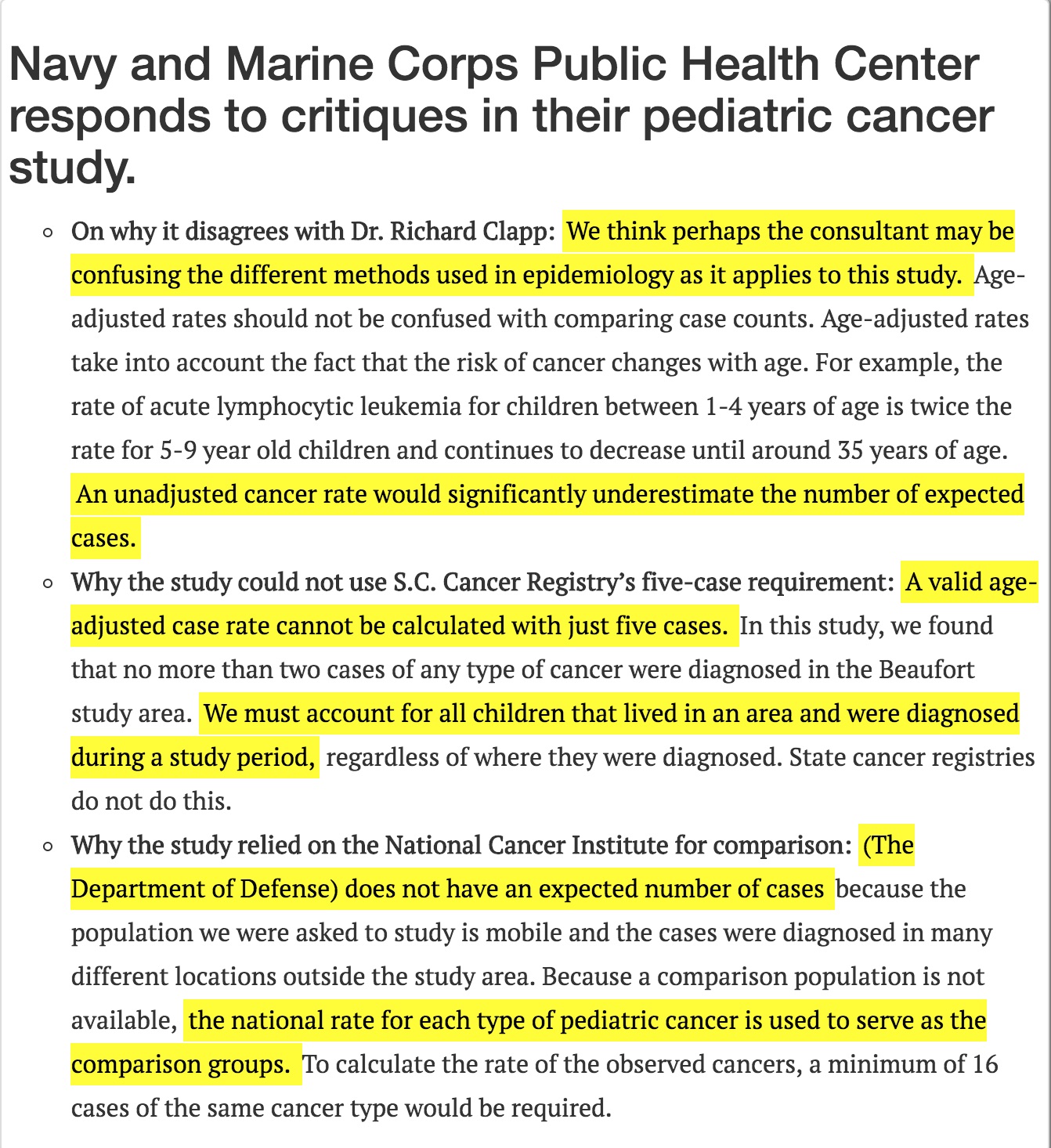

However, a former director of a state cancer registry interviewed by The Island Packet and The Beaufort Gazette raised questions about the Corps’ findings. And an official with the National Cancer Institute partially disputed the Corps’ explanation for requiring 16 cases.

“(The National Cancer Institute) requires a minimum of 16 cases to calculate a valid ratio, but actually the minimum of 16 cases requirement is to protect the confidentiality of patients so fewer than 16 cases are suppressed in our data release...There is not a simple rule of thumb to guarantee stability of rates or rate ratios, which depends on specific problems,” the National Cancer Institute official, who asked not to be identified, told the newspapers in an email.

Richard Clapp, an epidemiologist that has conducted more than 40 cancer studies and is the former director of the Massachusetts Cancer Registry, said he has never heard of a 16-case requirement. He pointed to studies done on as few as five confirmed cases to calculate a rate.

“This type of analysis could have been used in the (Laurel Bay) study,” he said in an email to the newspapers. “With small numbers of cases, the standard error may be large and the 95 percent confidence interval may be wide, but that doesn’t mean you can’t do the calculation.”

The Corps’ study looked at five different types of cancer: Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), Neuroblastoma, soft issue sarcoma and Wilms tumor.

South Carolina’s own Cancer Registry, run by the Department of Health and Environmental Control, calls for at least five cases or deaths of a disease in a geographic area for statistical stability.

In a written response to the Packet and Gazette, the Corps said it could not rely on DHEC’s method because it found “no more than two cases of any type of cancer” diagnosed in the Beaufort study area, though it did not list how many cases of each type it had confirmed, citing patient privacy.

Given the Corps’ explanation, 10 cases should have been confirmed — two cases for each of the five diseases studied — but the study cited 15 confirmed cases.

At the newspapers’ request, Clapp reviewed the Corps’ explanation of its cancer study.

“My reaction is that if this response was submitted as a homework assignment in a course I was teaching, I’d give it a C-,” the Boston University professor emeritus said in an email.

Clapp served on a federal board that reviewed contamination at Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune in North Carolina — one of the most notorious examples of military contamination.

A more comprehensive look, Clapp said, would be a cohort study that looks at “everything diagnosable.” Following repeated pleas from Lejeune residents, this type of study was done on Lejeune by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry , part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

A similar study could provide Laurel Bay residents with more reassurance, though Clapp acknowledged it’s more expensive and time-intensive.

Asked why the Laurel Bay study focused solely on pediatric cancer when scores of other residents reported illnesses, Rennix replied: “That wasn’t our question. So we can do the exact same thing with other illnesses, but that wasn’t the question we got. You could look at a zillion things and never make sense of anything, so you have to focus.”

The transience of the Laurel Bay community makes tracking medical conditions difficult. Residents are often stationed in Beaufort for a short time — a few months to a few years — and then move elsewhere.

The study originally identified 313 children with cancer who lived within a 30-mile radius around Laurel Bay and Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island from 2002 to 2016. Researchers found these children through a medical database, which included the children of active duty Marines across the country. However, it did not include Marine Corps members who have since left the service, a point some parents say downplays the findings.

Officials said that exclusion does not invalidate the results. Rather, they contend, the study’s purpose was to find the rate of childhood cancer, not to count the total number of children living on Laurel Bay who had developed cancer.

“As far as calculating a risk, we have to exclude people we can’t account for,” Rennix said. He implied that part of the parental questioning surrounding cancer at Laurel Bay is tied to the military’s tight-knit atmosphere.

“There’s no secrets; they talk; one thing leads to another,” Rennix said. “A lot of times in adults, they’re talking and ‘Gosh I’ve got this cancer,’ and ‘I’ve got this cancer,’ and they start thinking about their recent exposures and that question comes up. Sometimes they’re satisfied; sometimes they’re not.”

Kelly Meyerhofer: 843-706-8136, @KellyMeyerhofer

Next Story: A history of pollution on U.S. military bases

Toxic chemicals, jet fuel, oil, pesticides: the U.S. military's sordid history with housing its own