The contractions started at Applebee's, but Erica Bell refused to believe she was in labor.

It was September 2006, and she'd been having Braxton Hicks contractions for the past two months, made worse by a house that seemed to be holding onto a serious grudge against her family. Instead of going to the hospital, Erica stepped on her mother's foot to relieve the pressure (much to her mother's annoyance) and kept on eating.

But the contractions grew stronger, and after the family had gone home, Erica sat on her bathroom floor, vomiting in her toilet.

"She's gonna have this baby!" her mother shouted at Erica’s husband, Josh, who had fallen asleep although it was barely past 8 p.m. Her mother had moved in with Erica and Josh, a Marine, a few months earlier, to help with the 19-year-old’s difficult pregnancy.

Now, the three of them rushed to Beaufort Memorial Hospital.

It's true, most first-time mothers are scared before giving birth. But Erica had special reason to be terrified.

What if he comes out and something's not right, she thought. Could he have some sort of hemorrhage? Had he been growing properly? A heart problem? Was he breathing? Erica thought about the strange things that had happened to her house over the past three weeks. Would the baby be affected?

The two doctors attending Erica broke her water and gave her an epidural. Her left leg went numb, and Josh stood by her side to hold it up. Her mother was on her other side, holding her hand, giving her ice chips and washcloths as needed.

"Don't push like that," the doctors told her.

"I don't know the difference!" she snapped back.

It was a grueling 14 hours. The baby thought it best to come out feet first, but the doctors didn't agree. They turned him around as Erica — part numb from the epidural, part terrified — pushed.

Erica tried to remind herself that baby Jackson didn't know the difference between a fully-furnished or a bare house. He didn't know that his mother had been sleeping on the hard floor. And he certainly didn't know that only a few weeks earlier, his parents had lost almost everything they owned.

Erica and Josh lived on the Laurel Bay Marine housing community in Beaufort. Erica, who was studying criminal justice at the Technical College of the Lowcountry, and Josh, a lance corporal on the Marine Corps Air Station, had moved from Kansas City to Beaufort in December.

Erica, especially, was eager to decorate her new house. The two were young and didn't have much money, so their families had joined forces to gift them with furniture before their wedding. The house was big, Erica thought, or bigger than she expected. It had three bedrooms and a large kitchen and living room with off-white walls that she livened up with red, Japanese-inspired decor.

She took special care to furnish the nursery with a rocking chair, crib, bassinet in a Noah's Ark theme.

The house smelled fine, at first.

In late August, Erica and her mother were baking oatmeal cookies in the kitchen when they heard a loud pop, almost like an explosion.

"What the hell was that?" Erica asked her mother.

She wondered if a firecracker had blown up in the living room.

"Oh my God," she said as she watched clouds of white smoke coming from Josh's XBOX console and smelled a pungent, musty odor. "Mom."

Josh hadn't played the XBOX for days. Erica double checked the console; the XBOX had been turned off. OK, she thought. So it hadn't overheated. But the smoke kept coming from… somewhere. Erica and her mother opened the windows and doors to air out the house.

A maintenance worker arrived six hours after they called him. He checked the outlets without any tools. Nothing wrong there, he told them. He checked the water heater. Nothing wrong with it, either. Cable equipment. Nothing. The fridge? Nope.

Erica and Josh put the XBOX in the garage, but over the next several days, the putrid odor not only lingered, but grew more intense.

Erica and Josh started getting tired. Really tired. They took several naps during the day. Josh, who had never been a nap-taker before, would lie down during his lunch break, fall asleep, and then rush back to work so he wouldn't be late. And then there was the headache, Erica remembers. One heavy headache, like a brick tightening around her head, suffocating her, lasting for days. She vomited repeatedly and suffered from diarrhea and nausea.

Three days passed like this before maintenance measured the water heater temperature at 140 degrees and discovered that the Thermostat had burned from the inside out.

Maintenance replaced the Thermostat, and then instructed the Bells to clean the home with an industrial spray. That, they said, would solve it.

Erica was angry.

"I kept a very clean house," she remembered. "My house is not a dirty house. It’s very, very, very clean. So I’m like, what the heck am I going to clean?"

Nevertheless, the family didn't argue. They headed back to their house, wiped the walls, the furnishings. They vacuumed, they mopped. Eight-months pregnant Erica crawled on her hands and knees to clean the floor. But the odor was still there, and their headaches returned. In fact, all of the symptoms the family had experienced intensified.

Erica called maintenance that Saturday afternoon: She and her family needed out. Now.

The fire department was called. Firefighters, appalled to see a pregnant Erica in a house in such a dire condition, told property management to conduct mold testing while Erica and her family stayed at the Sleep Inn. Management agreed.

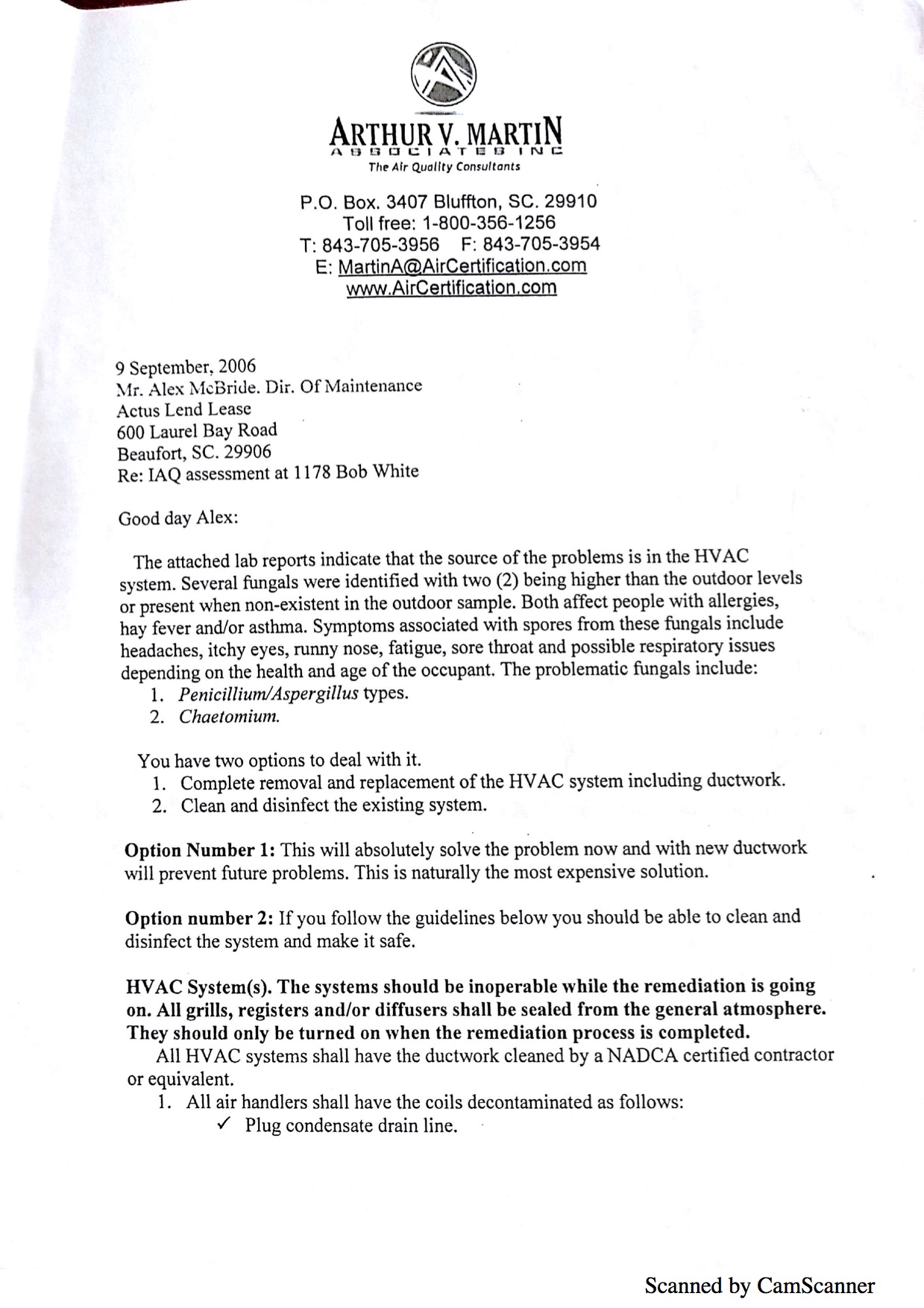

One week after Erica and Josh left their home, the test results returned. Two types of potentially hazardous mold — penicillium-aspergillus and chaetomium — were found within their HVAC system in elevated levels. Finally, AMCC, the property management company contracted with the Marines to manage Laurel Bay, agreed to move the Bells to a different home.

Erica and Josh's new house was just around the corner from their old home, which should have been an easy move. The smell slowed them down, though, and one of the movers developed a strong headache. Erica told him what had happened, and suggested that he go to the doctor.

"And then that's whenever she got mad," Erica said, speaking of an administrator from property management. "She told my husband not to spread rumors. And I told her that people had the right to know what was going on in my home."

The other hitch: Erica and Josh needed to throw away nearly all of their possessions, which had been stained with the nauseating odor.

"We had nothing," Erica said.

The Bells' renters insurance refused to cover the cost. AMCC gave Erica and Josh $250 for a relocation allowance, a fraction of the value of the Bells' lost items. The mattress, box springs, surround sound, TV, mattress pads, loveseat — all those items needed to be thrown away and rebought.

They drove to Charleston to buy another car seat, another stroller, another bassinet. Erica and Josh got their first credit card to cover the costs. Everything ended up costing over $3,000.

"Honest to god, we’re probably still paying off that darn credit card from the interest," Erica said.

A friend bought them three small black chairs that were meant to substitute as beds, but pregnant Erica couldn’t fit. She spent five days sleeping on the hard floor.

The company that tested for mold recommended that the HVAC system be entirely removed and replaced, so Erica was surprised to see another family moving into her old house within weeks after they had moved out. Erica noticed the family had a newborn.

Erica asked the new family if they knew the house's story. No, the man said. Property management said they'd done some hallway gutting and renovation, but that AMCC had taken care of everything.

So Erica told him the whole story. A few days later, Josh came home from work for lunch. He told Erica he’d been called into a higher-up’s office, and he’d been given an edict: “Tell your wife to shut her mouth and stop spreading rumors and lies. We don’t need a ruckus going in there."

AMCC property management — who declined a request by the newspapers to respond specifically to Erica’s claims — had tried to tell her nothing was wrong with her house, and that all she needed to do was clean. Now Marine higher ups were trying to make her believe she was crazy. She wasn't having it.

"They told us to keep our mouths shut, they didn’t believe us, they treated us like crap," she said. "What makes you think that... they told these people (the new residents) the truth?"

A week later, Erica was in the delivery room.

The nurse handed Jackson to Erica. Ten fingers, Erica counted. Ten toes. Two ears. A nose. Two eyes. A mouth.

"Maybe everything was going to be all right," she thought. "Maybe he is going to be OK." That sense of relief didn't last long.

Two weeks after Jackson was born, he seemed to constantly be spitting up, constantly suffering from acid reflux. The day after Christmas, Erica and Josh rushed 3-month-old Jackson to the ER when he caught pneumonia. He contracted pneumonia a second time in January, and then an upper respiratory infection in February, and he spent more time in the hospital because of a food allergy in April.

To make matters worse, Josh was deployed from July to December. Jackson's health worsened. The pediatricians wrote off Jackson's multiple hospital visits as consequences of Erica's inexperience.

"They kept telling me — all the times I took him to the ER, or took in him to the doctor — oh, you’re a first-time mom." Erica said. "They said, oh, this is normal."

It infuriated her. Why, she wondered, was everyone determined to make her believe she had lost her mind?

The worst of it came Dec. 20, 2007. Josh had returned, and the couple decided to celebrate at Outback Steakhouse. They first headed to their neighbor Christine's house to drop Jackson off, and Christine's elementary school daughters played with the now 15-month-old Jackson in a front room while the parents talked.

Erica heard a scream.

She ran to the kids and found Christine’s daughters shrieking and Jackson vomiting and foaming at the mouth, his eyes rolling back into his head.

"What the heck is going on with him?" Josh asked, panicked.

"This is what happens, this is what he does, this is why I've been trying to get you home," Erica said.

Josh scooped Jackson up into his arms and ran him back home. Jackson couldn't stop vomiting — when he had nothing left to throw up, he dry heaved. And then, all of a sudden, his lips turned blue. Jackson became unresponsive.

Erica called 911, and an ambulance took him away.

"He was steps away from being dead," Erica said.

This time, the doctors were able to diagnose Jackson with Eosinophilic Esophagitis, a disease that corrupts the simple task of swallowing and turns it into an agonizing process. The doctors instructed Erica to feed her son with EleCare, an expensive formula that the military did not cover at the time.

Doctors hadn’t (and still haven’t) confirmed a causal connection, yet Erica couldn't help but wonder: Did any of this have to do with the hazardous mold growing at her old house?

The Bells moved to Fort Worth, Texas, shortly after his non-responsive episode, and in January he was hospitalized again. He was diagnosed with other eosinophilic disorders, fructose malabsorption, and intestinal motility issues — essentially, for Jackson, eating was a near-impossible task.

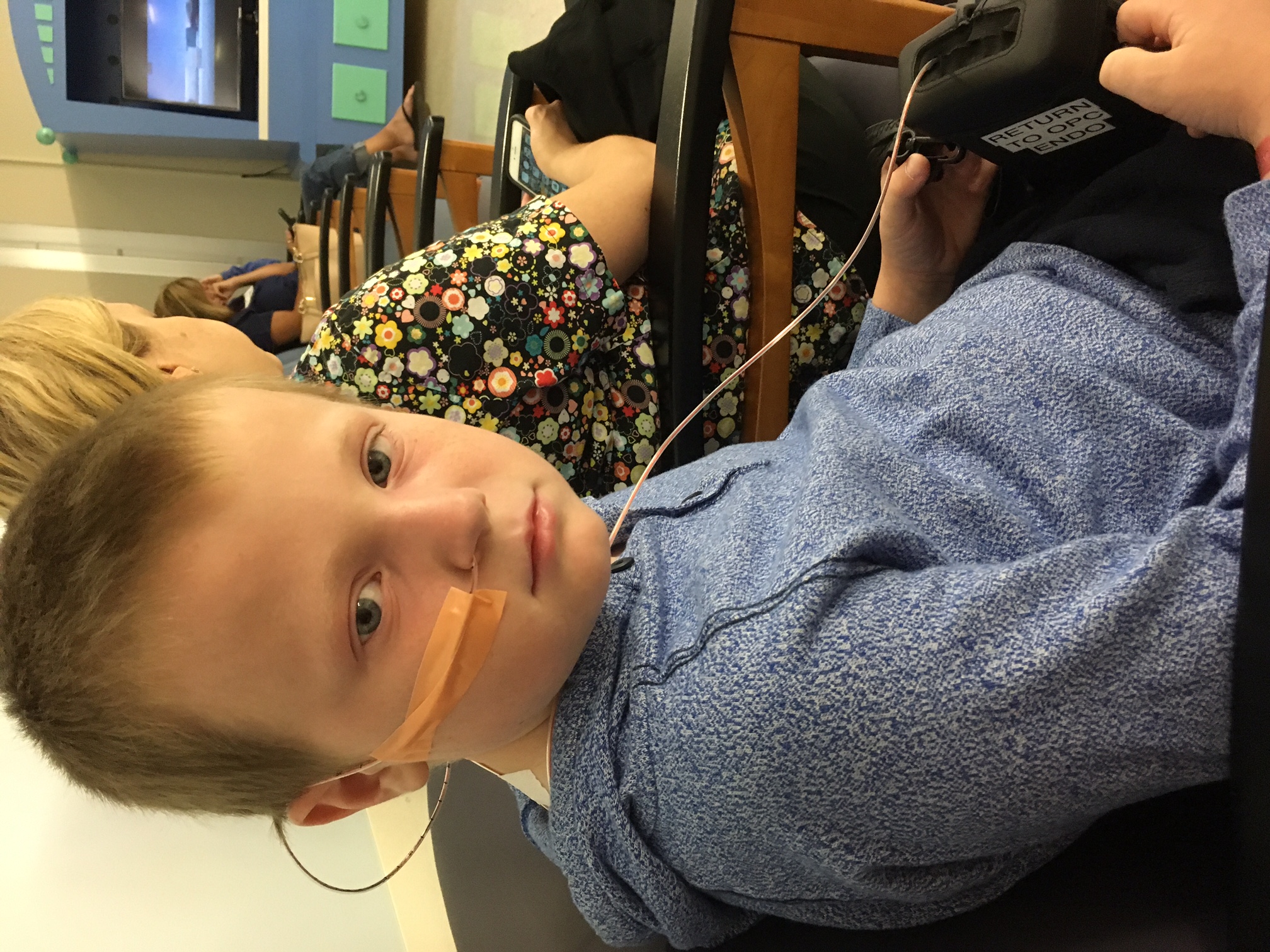

In March 2009, doctors gave 2-year-old Jackson a bronchoscopy, and they decided to put him on a feeding tube 24 hours a day, seven days a week. As he grew older, he was gradually allowed to wear the feeding tube from 8 p.m. until morning. Now, he can eat turkey, chicken, beef, cucumbers, potatoes and broccoli without the tube's help.

It's difficult being a kid who's different.

Jackson plays soccer with friends from the neighborhood, although he has to go inside and rest after half an hour of running around. Buttons are a challenge, as motor skills are difficult for him.

Holidays are tough, too. Although Jackson insists on going trick-or-treating every Halloween — most recently as the blue Power Ranger and Prince Philip from Sleeping Beauty — Erica can tell he doesn't enjoy it. He goes because he wants to be a "normal kid," Erica says. He knocks on a few doors but can't eat the candy. So he gives his spoils to the neighbors.

Life for Jackson is physically and mentally draining, but the boy still has spirit.

Once, in September 2013, with the family now in San Diego, Jackson slipped into a coma for more than 16 hours after, according to Erica, a doctor gave him an overdose of medication during a routine visit.

Erica was enraged. She threatened to get the doctor’s license revoked.

"I'm not 18 years old any more, and I'm not afraid to stand my ground," Erica said.

Jackson wasn't afraid to stand his ground, either. When he finally woke up, the doctor apologized and asked for a hug. Jackson kicked him in the shins instead.

Things began to turn around in May of 2014, when Jackson met legendary Olympic swimmer Michael Phelps.

The Make-A-Wish Foundation, a non-profit organization that gives experiences to children with life-threatening conditions, had told Jackson he could have one wish. Jackson aimed big. He told them he wanted to meet Michael Phelps, go to Hawaii, and swim with dolphins.

Make-A-Wish nearly came through perfectly. The only change? The trip was to Cabo, Mexico, rather than Hawaii. Jackson didn’t mind.

Jackson first met Phelps at a dinner hosted by the hotel, which consisted of upwards of 25 cucumbers, one of the few foods Jackson could digest on his own. Jackson was too nervous to eat at first, but Phelps talked him into it.

"Michael Phelps was like, 'You got to eat, buddy. You gotta eat. You’re going swimming with me later,'" Erica remembered.

Over the next three days, Jackson and Phelps became fast friends. Jackson swam with Phelps in an enormous pool 50 yards from the ocean. They attended a benefit dinner together, ate lunch, and went golfing.

"He was very patient, very loving to children,” Erica said. “And just gave our son a boost that he really needed."

Erica’s husband declined to talk about the family's story out of fear of retribution. But Erica says the mold, the silencing, Jackson's illnesses — all have taken a toll on her relationship with the Marine Corps.

"I respect my husband's job," Erica says upon reflection. "I respect what he does for the country, I respect that he is devoted to it. But at the same time, too, I don't respect the military higher officials."

She also hasn't forgiven AMCC or the Marine Corps for making her feel as if she was losing her grasp on reality.

In many ways, Erica still feels betrayed by the Marine Corps. In spite of Erica's protests, the military recently moved Josh and his family 100 miles away from San Diego, where Jackson still needs to visit for doctor's appointments. Erica drives to the city two or three times a week. She also has to fight for certain items not always covered by the military's health insurance — a medical stroller for Jackson when his energy and feet betray him would have put her back several thousand dollars without that fight.

"They need to do something," she added, not satisfied with a response that she believes is too little too late.

Today, Jackson is 11. He has gone through over 30 endoscopies, five hospitalizations, and takes 12 medications every day.

The family lives near San Diego, and Jackson has three healthy younger sisters. A nurse helps Erica and Jackson eight hours a day. For the first time in his life, Jackson began the school year at a public school. His principal and teachers are all understanding, and they give him extra time to accomplish tasks that other students take for granted. All of his teachers agree that he's an exceptionally smart kid.

Jackson confronts his illnesses every single day. He wins most days. But on the rare occasion, it’s simply too tiring to fight.

Erica remembers one particular day when Jackson was 7. He came home, walked straight to his room and shut the door.

A few hours passed, and Jackson hadn't yet come out. This was unusual. Nighttime approached, and Erica gently opened Jackson's door and peeked inside. He was sitting on the floor, playing with lego figurines.

"Do you want to come out?" she asked him.

"No."

"Well, what are you doing in there?"

"I just want to be left alone."

Erica grew impatient.

"What is the matter with you, Jackson?" she said, losing her temper.

"I want to die," Jackson responded matter-of-factly.

Erica stared.

"Jackson, you can't die," she said. "Why do you feel this way?"

"Because I'm done, Mommy," Jackson said. "I don't want to do this anymore. I just want to go to heaven."

"I know that in heaven, I won't have this tube," he continued. "I won't be sick. I'll be clean, and I don't have to deal with any of this."

"It had gotten to him," Erica remembers now. "He had only been to kindergarten, he was having a hard time with it, he was noticing how different he was from everybody else."

Erica sat down, spoke to her son, and cried with him. By the end of the school year, Jackson would meet Michael Phelps. His father would return from deployment, and he'd be happier and healthier. But he didn't know that yet, and neither did Erica.

Some days are harder than others. And that day, Erica says, still haunts her.

Kasia Kovacs: 843-706-8139, @kasiakovacs

Next Story: The Laurel Bay Health Study