Over the past 60 years, thousands of military families have quietly lived behind the secure gates of Laurel Bay, a community of about 1,100 homes and several schools tucked along the Broad River near the Marine Corps Air Station in northern Beaufort County.

Their spouses and other loved ones assigned to MCAS or the Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island a few miles to the south work diligently to help ensure America’s security.

Yet the U.S. military over the years kept Laurel Bay residents largely uninformed about the specifics of potentially widespread environmental contamination where they were living. And although a causal connection between the contamination and illnesses has not been established, many residents now fear the brew of pollutants has made them or their children sick.

Adults and children have battled cancer. Mothers have suffered through stillbirths, miscarriages and fertility issues. Others have reported serious respiratory, digestive and blood disorders.

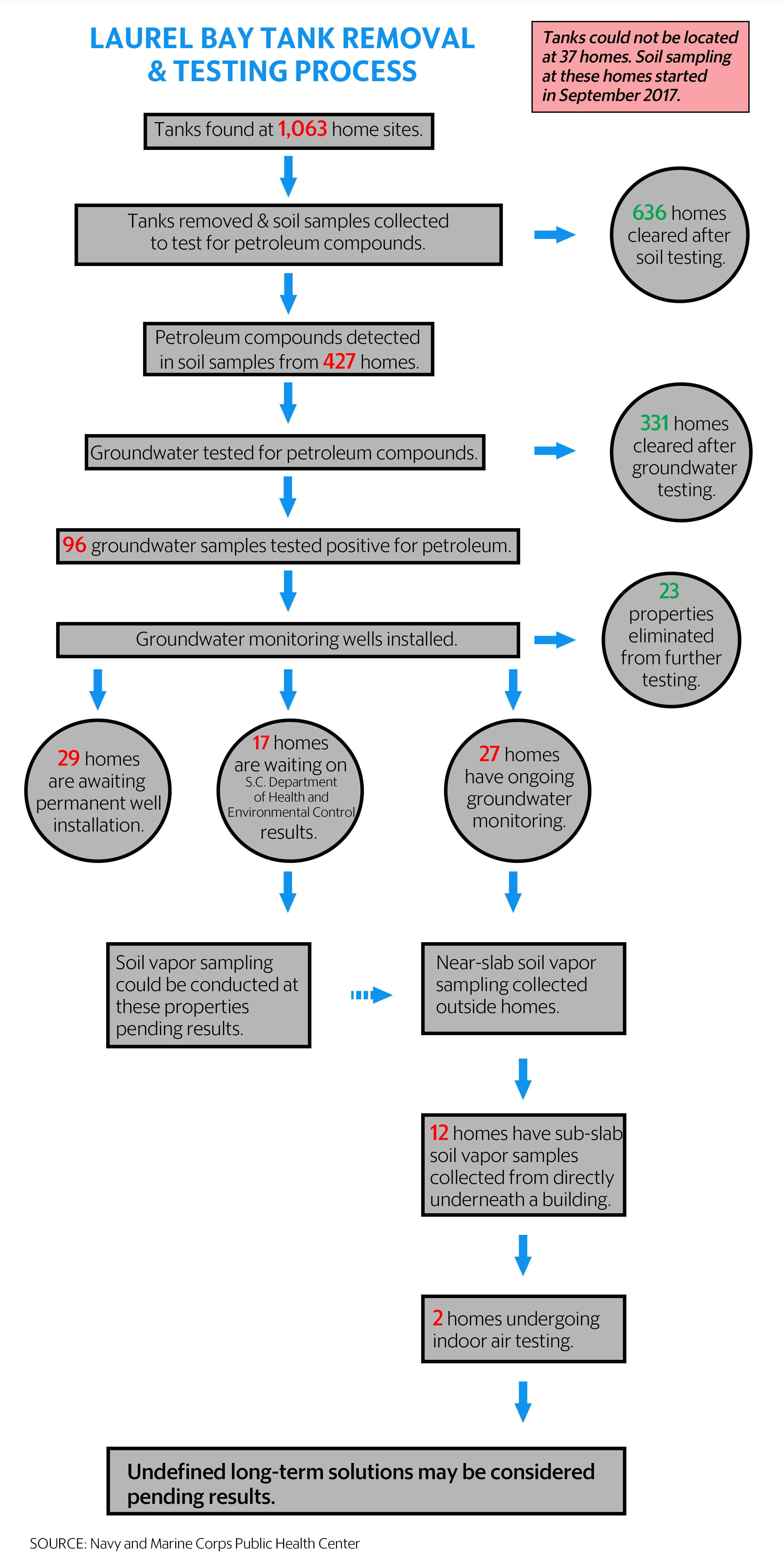

In the past decade, four in 10 Laurel Bay addresses tested for contamination posted higher-than-recommended levels of petroleum compounds in initial soil samples, according to military records reviewed by The Island Packet and The Beaufort Gazette. Follow-up tests showed far less risk of contamination for 90 percent of the addresses tested.

Those compounds include a known carcinogen and a possible carcinogen suspected of leaking out of hundreds of corroded and abandoned heating oil tanks buried beneath the yards of Laurel Bay homes.

Other potential contamination is lurking in plain sight, according to a months-long investigation by the newspapers, including:

- Mold, including at least two cases of verified harmful mold. Residents interviewed by the newspapers say Laurel Bay property managers offered only Band-Aid solutions to the problem. At least one family moved out of their home because potentially dangerous mold was growing at elevated levels.

- A powerful pesticide that was applied outside homes until 1995 — seven years after it was banned in the U.S. because it was considered harmful to both human health and the environment.

- Lead-based paint found in a childcare center, on nine playgrounds and on the window sills, ceilings and structural beams of Laurel Bay homes built in the 1950s; and asbestos in floor tiles and exterior caulking.

Laurel Bay “belongs in a Petri dish,” a Marine Corps member wrote in a Facebook group for concerned Laurel Bay parents.

The area not far outside Laurel Bay’s gates has also been cause for contamination concerns.

Multiple locations within several miles of Laurel Bay have been designated as federal Superfund sites, polluted areas flagged by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as a priority for cleanup. MCAS and Parris Island each have numerous hazardous waste sites requiring long-term cleanup.

Military officials, who have conducted various tests in recent years, say the presence of contamination in Laurel Bay is not enough to make residents sick because there must also be a pathway to exposure. State officials, who have overseen the testing, agree.

The heating oil tanks were buried several feet underground so residents did not come in contact with the petroleum compounds, contend the officials. They also maintain there is no threat to the community’s water supply because residents have used a public water system for decades. They add that threats from mold, pesticides, lead and asbestos have been abated. More military testing and long-term monitoring — under the state’s oversight — is still ongoing at several dozen homes.

But experts contacted by the Packet and Gazette say the Marines’ study of heating oil tanks did too few tests on the majority of homes to draw such sound conclusions — likely in an effort to save time and money.

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly how many families have lived in the roughly 1,100-home neighborhood over the past 60 years and are now sick. Families moved in, stayed for a few months or years, and then moved away.

Many of these former and current residents distrust Marine Corps officials because they perceive officials have been previously silent on the contamination.

“How can you (the Marine Corps) sit here and pretend like you knew nothing? When you did, you did, you did know!” said Erica Bell, a mother who was pregnant with her son while living on Laurel Bay in 2006.

“And now they just want to brush it all off, like it’s no big deal,” Bell continued. “No big deal! We have children who are sick. … These are men and women who protect our freedom. And they deserve a nice place to live.”

Moreover, many residents are scared to speak out about their observations and concerns, emails show. They fear reprisal from Marine Corps authorities, particularly if they or their spouses are on active duty.

“Speaking out is not an option, it is a necessity and doing so makes us vulnerable to backlashes, intimidation and possible retaliation that may endanger my husband’s career and retirement,” a resident, whose name was redacted, wrote in an email to military officials in January.

An MCAS spokesman passed off most of the newspapers’ questions to the Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center, which conducted a 28-month health study that was publicly released in October.

“The health and welfare of our Marines, Sailors, their families and our civilian workers is, and will continue to be, paramount,” Capt. Clay Groover wrote in an email. “We are using the information, findings, and recommendations of the study to guide continued efforts to provide safe and healthy housing.”

The Packet and Gazette began its investigation in January after former Laurel Bay resident Amanda Whatley posted a YouTube video questioning whether her daughter’s leukemia was caused by the contamination.

Whatley and 10 other ex-residents later filed a lawsuit against private companies that managed the housing complex, alleging the defendants were aware of serious contamination at the housing site, but failed to adequately inform residents.

The plaintiffs’ Hilton Head Island attorney, Robert Metro, told the newspapers that given the pending litigation, his clients would be unavailable for comment for this series.

Atlantic Marine Corps Communities — the property management company for Laurel Bay and one of the defendants in the lawsuit — filed a motion in November to dismiss the suit.

Among other things in its motion, AMCC contends that it shouldn’t be held liable for any of the “alleged acts” because it was a contractor for the Navy and was in “compliance with federal directions.”

AMCC did not respond to specific allegations when contacted by the Packet and Gazette, but provided the following written statement to the newspapers:

“AMCC is fully committed to the environmental health and safety of our residents. We investigate all resident complaints to ensure that they are properly addressed in a timely manner. AMCC continues to be proactive in responding to any concerns expressed by our families. Our responses to these concerns, as in all resident issues, are our highest priority. AMCC declines to further publicly comment due to active litigation.”

'We were never told'

Past and present Laurel Bay residents interviewed by the newspapers say they were left in the dark about the contamination leaking from old heating oil tanks and found in the soil and groundwater under their yards. According to military and state records, the contaminants included:

- Naphthalene, a compound found in traditional moth balls, insecticides and fuels, that has been shown to cause cancer in lab animals and is considered a possible human carcinogen, according to the EPA. To date, the highest naphthalene reading found at a Laurel Bay address is 1,030 micrograms per liter — 41 times the S.C. Department of Health and Environmental Control’s screening level of 25 micrograms per liter. Forty-four out of nearly 300 Laurel Bay properties posted naphthalene readings above DHEC’s screening level, according to a sample of initial groundwater test results from 2010 to 2016 that was reviewed by the newspapers.

- Benzene, a known carcinogen found in petroleum products, that can cause serious damage to the central nervous system. The highest benzene reading found at a Laurel Bay address has been 30 micrograms per liter — six times DHEC’s 5 micrograms per liter screening level. And five out of nearly 300 sampled addresses posted benzene levels exceeding DHEC's screening limit, according to the papers’ review.

- Free product was found at 23 of the nearly 300 sampled properties. The petroleum product does not mix with soil or water.

Both state and military officials say the levels of naphthalene, benzene and free product do not pose a threat to residents, especially because the tanks were buried several feet below ground. And all addresses that tested above the screening levels have had — or will soon have — additional testing performed to ensure residents’ safety, according to the officials.

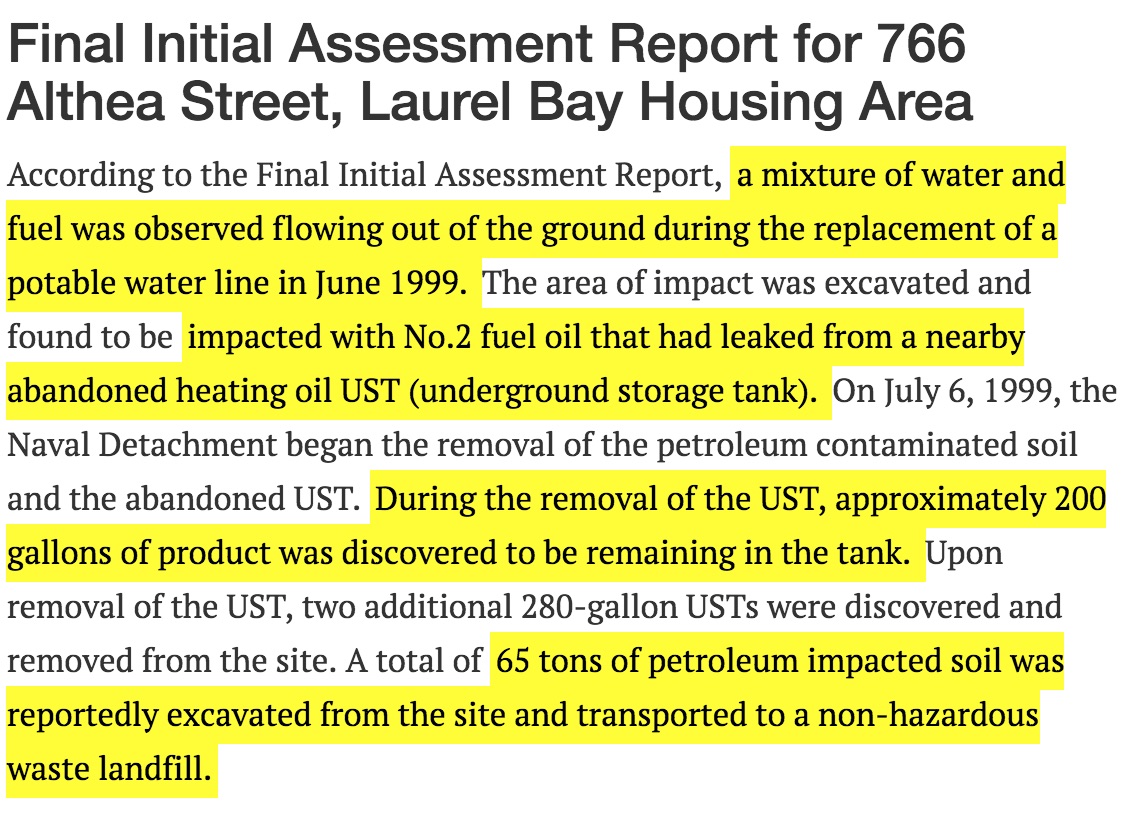

Still, residents say they had a right to know about contamination that was first discovered in 1999 when construction workers began digging up and removing a few underground storage tanks for a utility construction project.

Construction workers excavated three oil tanks — one of which had 200 gallons of fuel still inside — and removed 65 tons of petroleum-impacted soil. Two years later, workers discovered three more oil tanks and 20 cubic yards of contaminated soil at another home, which they removed.

A 2001 environmental survey recommended the Marine Corps remove remaining underground oil tanks, associated piping and any remaining fuel. But the Corps did not begin systematically removing the tanks until 2007, and many residents had to wait another 10 years before learning about the contamination. That's when Whatley's YouTube video caught the attention of Marine Corps members and their spouses on Facebook.

To watch Whatley's full video, click here .

Whatley, the wife of a U.S. Marine previously stationed at Parris Island, described the 2015 leukemia diagnosis of her daughter, Katie.

Whatley speculated that her daughter’s illness may have something to do with the family living on Laurel Bay from 2007 until 2010, when carcinogenic substances may have leaked out of the underground heating oil tanks.

“(If I’d) had in the back of my mind that cancer was happening to children who lived where we lived, I would have taken (Katie) to the doctor so much sooner,” Whatley said in a YouTube video posted in January. It would have “spared her a lot of pain and suffering, and a very unclear future.”

The newspapers’ review of records found no evidence that the military consistently sent community-wide notifications to residents about specifics of the contamination being found in their yards before Whatley’s video was released.

The earliest note sent to residents about the tanks came from the neighborhood’s property management company in June 2010, according to records provided to the newspapers. Although the letter notified residents that tanks would be removed, it made no mention of the contamination and framed tank removal as a safety issue.

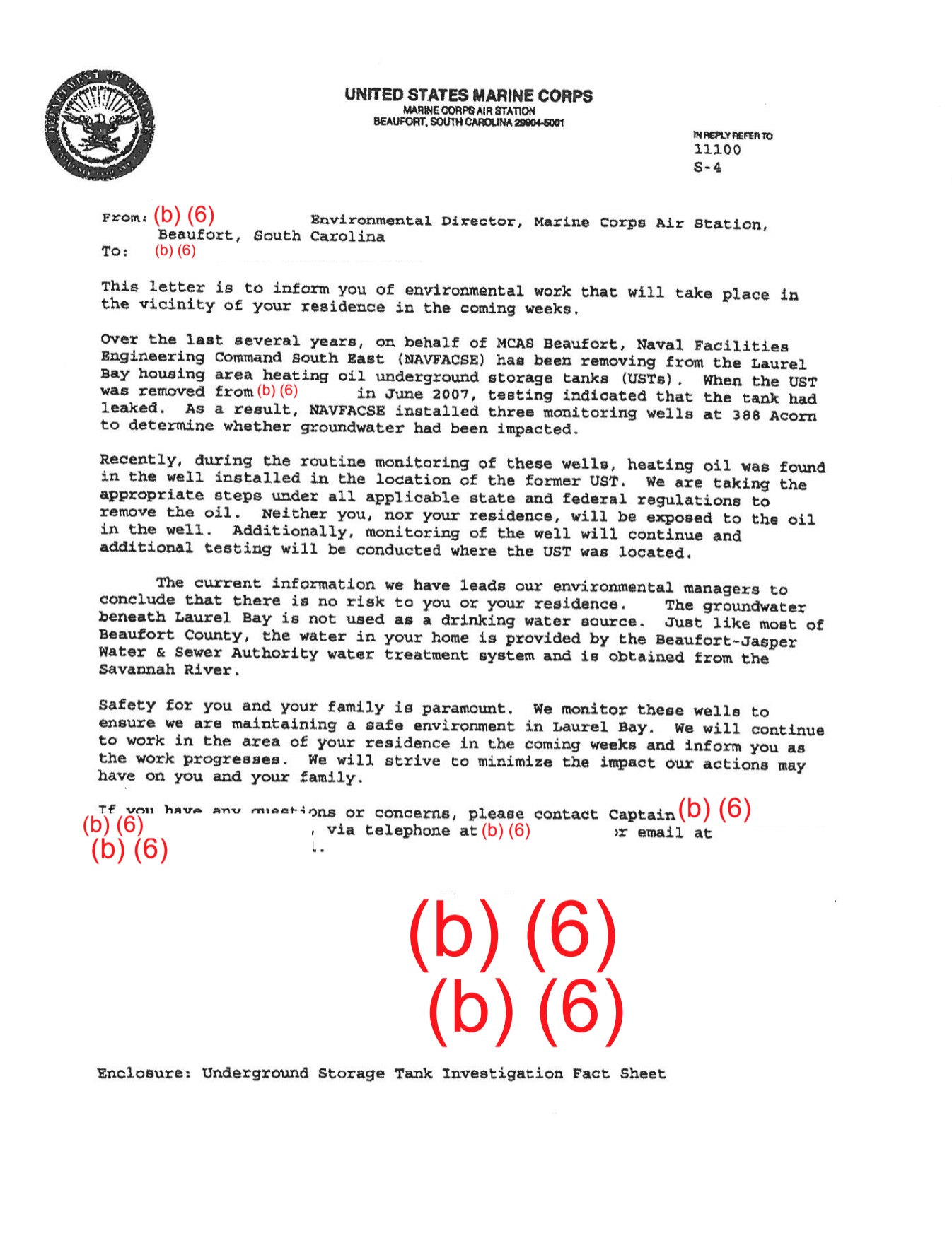

Contamination was implied in an undated letter from MCAS Beaufort, likely sent in 2013 because it noted that vapor testing would begin in November 2013, according to those records. The letter was addressed to residents living in the vicinity of upcoming “environmental work,” and noted a tank leak at one residence where oil would be removed that November. The letter did not mention benzene or naphthalene and stated, “there is no risk to you or your residence.”

In an April 2016 letter inviting residents to a town hall about soil gas testing, MCAS officials said the tanks may have leaked, but again failed to include specifics about benzene and naphthalene.

In spite of these notifications, more than a dozen current and former residents interviewed by the newspapers said they knew nothing about the contamination before Whatley’s video went viral. Records show some residents sent multiple emails pleading for the testing results of their individual address before officials supplied the results.

“Is it just me, or has anyone else lived here 2 years and Ms Whatley’s video was the first you’d heard of this?’ one Laurel Bay resident wrote on social media in January, just after Whatley’s YouTube video went viral. “If this truly is an investigation that’s been going on for shy of a year now, more effort should have been taken on behalf of the Marine Corps to be certain ALL families were aware of it. Informed people make informed decisions.”

Had they known, some say they would have moved out — or never moved in.

One current Laurel Bay resident, who asked to remain anonymous out of fear of retaliation against her active duty husband, said she has chosen not to have children while living in Laurel Bay because of the contamination.

“We don’t want to have children until we leave Laurel Bay,” she said. “We don’t want them to be exposed to this right now.”

If the couple does become pregnant for an unexpected reason, she added, they would move away “just for our sanity.”

Experts agree that residents should have been informed about the petroleum-based chemicals leaking beneath their neighborhood.

“Conclusions that the contamination is not a health threat, even if proven, do not justify the failure to inform people,” said Lenny Siegel, executive director for the Center for Public Environmental Oversight, a California-based nonprofit that promotes community oversight of cleanup at military facilities across the U.S.

Further, in at least two instances, authorities at Laurel Bay allegedly attempted to silence people from sharing their observations.

Then-resident Erica Bell said she was told to “shut up” when she tried to warn others about her experience with elevated levels of harmful mold growing in her house. She said she was told to keep quiet once by a woman who worked for the property management company, and once by a Marine who worked with her husband.

And a former maintenance worker who worked for the property management company on Laurel Bay in 2005 said his supervisor told him to keep quiet when he noticed something strange with a geothermal heating system. The geothermal unit started spewing water, bringing oil-soaked soil to the ground’s surface. A colleague told him that the oil was from the abandoned underground oil tanks.

The maintenance worker, who spoke to the newspapers on the condition of anonymity, said he noticed that the contaminated water and smell of oil spread to more than one property, seeping into adjacent yards. But when he brought it up with his supervisor, he was told not to speak about it.

In response to the allegations of silencing, the Marine Corps said in a statement: “The Marine Corps does not tolerate negative action in response to someone speaking out about potential health concerns or concerns about their family’s living conditions. We encourage anyone with a health issue to contact their health care provider, and if there is a concern with conditions at housing, to seek correction through the terms of their lease and bring it to our attention if our assistance is desired.”

AMCC declined to comment on these specific allegations.

Hundreds of leaky oil tanks

At least 930 of the more than 1,200 known tanks buried beneath residents’ backyards were corroded with pitting and holes, records show. One tank had an “approximately 12-inch by 40-inch opening” on its top.

The tanks, which date back to the 1950s when the housing community was built, were no longer used after the 1980s. Fifty years ago, if one oil tank started leaking or malfunctioning, maintenance workers emptied the tank, filled it with sand and placed another in the ground close to the original, according to MCAS Beaufort environmental affairs officer Billy Drawdy.

But in at least 79 cases, records show maintenance workers did not patch the malfunctioning oil tanks and left them in place with oil inside.

That detail seems to only have been communicated to residents once in a brief footnote from a 2010 letter, according to records provided to the newspapers. In a more recent fact sheet published on the Marine Corps Beaufort website in October, however, officials wrote: “As was the accepted practice at the time, (underground storage tanks) were drained, filled with dirt, and left in place when they were removed from service.” No mention was made of the nearly 80 oil tanks with fluid left inside.

Complicating matters are the possibility of missing tanks and discrepancies in records. The Marine Corps says 1,252 tanks have been located and removed. Yet in 2002, when the Department of the Navy contracted with CH2M Hill Constructors, Inc., to locate the tanks, the contractors estimated 1,400 underground storage tanks were buried underneath Laurel Bay.

“I cannot address the 1,400 number,” Drawdy said. “The 1,252 number is the number that we have removed since we started this project back in 2001. That is all known tanks.”

The Marine Corps originally had documentation about where the tanks were buried from the 1950s, but information in those reports was not accurate, Drawdy said. When a new tank was installed to replace one that was malfunctioning, many of those additional tanks “were installed without documentation,” records show.

Without records, Marine Corps officials used a few different techniques to find the storage tanks: A metal probe that scans the ground, a ground-penetrating radar and a magnetometer.

The military’s study released in October acknowledged that tanks could not be located at 37 homes. Soil sampling for those homes started in September, officials said.

“You can never be 100 percent (certain), but we’re as confident as we can be,” Drawdy said when pressed on whether all tanks had been discovered and removed.

Military and state health officials maintain that since tanks were buried more than five feet underground, contamination posed no health risk to residents.

“The tanks were buried deep underground, meaning residents were never exposed,” said Fran Marshall, a toxicologist for the S.C. Department of Health and Environmental Control, which is overseeing the testing.

But records show not all tanks were buried that deep. In at least 124 cases, the tanks’ bases were buried less than five feet from the ground’s surface, and in at least 10 instances, the bases of the tanks were less than four feet underground, according to military records reviewed by the newspapers.

Too few tests done?

Few Laurel Bay homes received soil vapor sampling, a type of test that at least one expert says is crucial to understanding the extent of contamination.

More than 400 of the roughly 1,100 Laurel Bay homes failed initial tests that measured the amount of petroleum compounds in soil, records show. The tests began to be removed from the ground basewide in 2007 as a “matter of good stewardship,” Corps officials have said.

Records show that of the 427 addresses tested for petroleum levels in groundwater, 96 failed and had wells installed to monitor groundwater as contaminants gradually biodegrade over time.

If a property failed the well reading, then the home moved on to soil vapor sampling — which measures if chemicals in soil and groundwater have migrated around the outside of a building — and indoor air sampling, which measures if vapors have moved inside a building.

Cracks in a building’s foundation increases the likelihood of vapor intrusion. Sealing those cracks is a suggested remedy to reduce the risk of vapor intrusion, experts say, but it’s unclear if the military or private contractors that manage Laurel Bay’s housing took that step.

A former Laurel Bay resident who lived on base in 2014 and 2015 posted pictures of mud seeping through cracks in her home’s floor.

“Housing just put carpet over (it),” she wrote in a closed Facebook group for Marine families.

Under the military’s methodology, a property has to fail three separate tests before being tested for vapor intrusion, an elimination-style testing design that experts contend does not provide a holistic scope of the situation.

Reserving the soil vapor sampling for one of the last rounds of testing is “backwards,” according to Larry Schnapf, an environmental business lawyer and adjunct professor of environmental law at New York Law School.

Even if chemicals found in soil or groundwater are below recommended levels, that doesn’t necessarily mean vapor intrusion has not occurred, Schnapf said. He suspects in the Laurel Bay study, the military waited to do vapor testing at the end partly to save money.

“There’s a real resistance to do vapor intrusion because it leads down a path,” Schnapf said. “If the Department of Defense did (soil vapor sampling at every site), it’d be a lot of money.”

Instead, the Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center’s methodology relies on the practice of testing soil first, then groundwater, then conducting vapor sampling.

“(They’re) using a very simple screening tool that doesn’t capture the complexity of the pathway that we know of today,” Schnapf said.

The Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center stands by its testing methods.

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that investigates environmental health threats, recommends more lines of evidence to “confirm with reasonable certainty that there are no health concerns.”

EPA guidelines published in June 2015 — the same month the Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center began investigating potential environmental exposures in response to residents’ concerns — offer similar recommendations.

Although those involved with the Laurel Bay Health Study say that exposure to pollutants was unlikely, there are several instances in which residents suspect they were susceptible to the contamination.

Residents reportedly drank and used water from a supply well located on Laurel Bay until the 1970s when the well was capped and Beaufort Jasper Water and Sewer Authority took over, records show. That would have been roughly the same time period when the heating oil tanks were used — many of which eventually corroded and leaked.

Also, records detail an incident in June 1999 when “a mixture of water and fuel was observed flowing out of the ground during the replacement of a potable water line.” That fuel had been leaked from a nearby abandoned oil tank, the Marine Corps discovered.

Pesticides used after ban

Benzene and naphthalene weren’t the only dangerous substances found on Laurel Bay.

The pesticide chlordane was routinely used until 1995 — seven years after it was banned by the U.S. government in 1988, records show.

Chlordane was once considered to be a sort of “magic bullet,” killing termites and other insects, but the EPA released a study in 1984 that found chlordance caused cancer in laboratory animals. The pesticide is considered a human health risk, especially to the nervous system, digestive system and the liver, ATSDR reports.

Chlordane has also been linked to ovarian and uterine diseases, although researchers haven’t been able to confirm chlordane is the sole cause of those problems, according to the EPA.

ATSDR says chlordane can remain in soils more than 20 years after use. That’s true of Laurel Bay. Records show chlordane was found in the ground at several demolished Laurel Bay home sites in 2014 — about 25 years after its use was banned by the federal government.

But records published as early as 2002 warned about Laurel Bay’s use of chlordane after its ban. A 2015 report noted that chlordane and an insecticide, heptachlor, “exceeded screening levels,” though the report also noted chlordane’s risk level was too low to be considered a threat to human health.

A noxious brew: Lead paint and asbestos

Laurel Bay residents — particularly children — faced other potential environmental threats where they lived and played.

A 2001 report noted chipping lead paint in nine playgrounds and a childcare center on Laurel Bay, places where children are the most vulnerable — especially young children, who are prone to touching or chewing on peeling paint chips.

Records show the childcare center was “of particular concern,” with the building’s exterior containing “extensive peeling of possible (lead-based paint) and paint chips" that were “abundant” in the soil. The lawsuit filed against AMCC notes this “poses a potential threat to the health of many children present on the property.”

Peeling paint was observed in the wood framing of screened porches and windows in housing, too, records show.

Laurel Bay authorities encapsulated 118 residences in 2008, a process that involves painting a liquid coating over lead paint to serve as a barrier.

Authorities enclosed, or sealed off, surfaces with lead-based paint at 23 homes. They also removed materials with lead-based paint in six houses, according to records, and demolished five of the homes between 2003 and 2004.

Painted surfaces inside and outside of MCAS Beaufort Child Development Center tested negative for lead paint in December 2008, Corps spokesman Groover wrote in an email.

He added that the two child development centers and the Laurel Bay Youth Center are in compliance with federal lead regulations, though it’s not clear whether the playgrounds are a part of the centers that fall under MCAS purview.

Under the terms of its lease agreement, AMCC is required to have a lead paint management plan, but that plan does not require sampling for lead paint in each home, according to the Public Health Review.

Exposure to lead can lead to several health risks in children, including behavioral and health problems, slow growth, lower IQ and hyperactivity, hearing problems and anemia. Adults exposed to lead paint can suffer from increased blood pressure and decreased kidney function.

Pregnant women are especially at risk of delivering prematurely or exposing the fetus to lead, resulting in major health defects for the child, the EPA notes.

The Laurel Bay homes not only contained lead paint but asbestos as well in floor tiles and exterior caulking, and potentially in window caulking and insulation, according to records.

Like lead paint, asbestos becomes a risk when it deteriorates. If asbestos is inhaled, it can scar the lungs and cause lung cancer, according to the ATSDR.

Records show maintenance conducted asbestos surveys before demolishing houses in 2015, but it’s unclear whether they conducted asbestos surveys before renovating them.

“AMCC, they are the ones responsible (for abatement),” Drawdy said. “They have an asbestos management plan. They have a lead paint management plan. That is under their purview.”

Citing its pending litigation, AMCC declined to provide a current copy of a Laurel Bay lease. A lease obtained by the newspapers from 2006 noted units “may contain asbestos containing materials” with a similar addendum for lead paint.

"I just want answers"

Perhaps the most visible hazard on Laurel Bay is mold.

Dangerous mold was detected at elevated levels in at least two houses, records show. Testing by the military found that stachybotrys chartarum, more commonly known as black mold, was found in one home where “several resident occupants” had been “diagnosed with multiple cases of pneumonia.”

Two types of mold — penicillium/aspergillus and chaetomium — were found at elevated levels at another home in 2006. The home's residents experienced headaches, fatigue and severe nausea; the family moved out a few days after the mold was detected, according to a letter from the military.

The Marine Corps tested six Laurel Bay homes in 2012, and mold was detected in all six. Mold concentrations ranged from “marginal to acceptable” for indoor air, test results show.

Mold is relatively common in the humidity-saturated state of South Carolina. Treated properly, mold generally is not a threat to human health.

Drawdy said resident leases include a tip sheet on how to properly address mold. And AMCC carries out additional mold inspections at the request of residents, Groover wrote in an email.

But some former residents worry property management didn’t effectively respond to mold problems.

The AMCC lease from 2006 notes that if “evidence of mold or mildew-like growth in the Unit cannot be removed simply by applying a common household cleaner” and if the house had “musty odors,” among other conditions, then “management will respond in accordance with state law and the Lease to repair or remedy if necessary.”

The lawsuit filed against AMCC alleges “defects” in Laurel Bay homes, such as “faulty drains which cause moisture to ‘wick up’ into slabs” that promote mold growth.

Again, AMCC declined to comment on the specifics of the lawsuit.

“There was so much mold in those old houses,” said Jennifer, a former resident who asked that her last name be kept private out of fear of retaliation against her husband, who is still an active duty Marine.

“You could scrub and get rid of it for awhile,” she said. “And you could make a complaint and they (the property management company) would come and paint over it. Then, you’d give it a couple of weeks and it would be back.”

Jennifer said her daughter developed a persistent cough for two years during the family’s time on Laurel Bay. Today, all three of her children have asthma.

Jennifer said she wants more answers from military officials. In August, a Laurel Bay resident pleaded the same in an email to the Corps, echoing a sentiment felt by many.

“Sympathy doesn’t save others from illness and injury,” the woman, whose name was redacted, wrote in the email. “I feel you use it in an effort to silence my questions.

“I do not seek sympathy. … I just want answers to my questions.”

Kelly Meyerhofer: 843-706-8136, @KellyMeyerhofer

Kasia Kovacs: 843-706-8139, @kasiakovacs

Stephen Fastenau: 843-706-8182, @IPBG_Stephen

Gina Smith: 803-414-1340, @GinaNSmith

You think you've been exposed. What should you do?

If you believe you have been exposed to contamination, you should consult with a physician. Your doctor, for example, can conduct several medical tests to test for benzene, although these tests sometimes have trouble detecting exposure unless it happened recently.

Laurel Bay currently gets its water from Beaufort-Jasper Water and Sewer Authority — not from groundwater on site. The water is safe, and meets or exceeds all state and federal regulations, agency spokeswoman Pam Flasch said in an email.

Concerned residents can petition the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry to do a community health study, said Elena Craft, a scientist with the Environmental Defense Fund. Details on how to petition the ATSDR can be found here .

How we reported this series

In January, Amanda Whatley posted a YouTube video describing her time as a Laurel Bay resident and questioning whether her daughter’s leukemia diagnosis was caused by the contamination on base. Shortly after Whatley’s video went viral, The Island Packet and The Beaufort Gazette began investigating health and environmental conditions on Laurel Bay. Reporters submitted federal and state Freedom of Information Act requests to the S.C. Department of Health and Environmental Control, U.S. Department of the Navy and U.S. Marine Corps, and received more than 5,700 pages of records in response.

Key records referenced in this story include:

- Soil and groundwater test results for Laurel Bay homes from May 2014 to March 2017.

- Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center’s “Public Health Review Report of Laurel Bay Housing,” September 2017.

- Correspondence between Marine Corps officials, private contracting companies and S.C. DHEC officials.

- 2001 Environmental Baseline Survey for Housing Public/Private Venture in Beaufort, South Carolina, Department of the Navy Southern Division and Project Resources Inc.

- 2002 Phase I Environmental Site Assessment, URS Corporation contracted for the Marine Corps Air Station and Laurel Bay in Beaufort.

- Emails sent by Laurel Bay residents to Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort officials from 2016 to 2017.

- Environmental Protection Agency’s “Guidelines for Addressing Petroleum Vapor Intrusion,” June 2015.

- Class-action lawsuit filed against the Atlantic Marine Corps Communities, LLC, on behalf of Laurel Bay residents.

- EPA records on Superfund sites in Beaufort County.

- Nearly 1,000 underground storage tank assessment reports from S.C. DHEC.

In addition, more than 50 people were interviewed for this series, including former and current Laurel Bay residents, current and former Laurel Bay teachers, Marine Corps officials, Department of Defense officials, S.C. DHEC and other officials. Reporters also interviewed environmental health experts, professors, scientists and advocates.

A reporter traveled to Atlanta and Chesapeake, Va., to interview two former Laurel Bay residents. A photographer based in California took photos of a former resident who lives in Moreno Valley, Calif. Two reporters also gained access to a private Facebook group for Marine families with permission of the page’s administrators.

The Marine Corps made themselves available for one interview in early October. After holding a town hall meeting for residents earlier that evening, officials shepherded Packet and Gazette reporters into a van and drove them through Laurel Bay’s gates for one opportunity to ask officials questions, from approximately 8:30 to 10 p.m. The military required additional correspondence to be submitted by email.

Next Story: This 11-year-old was born in Laurel Bay. He now suffers from multiple medical conditions.

"I'm done, Mommy. I just want to go to Heaven," he said. He was only 7.