In many ways, Becca and Jerrico Satryan’s love story is typical of the Marine Corps: They met in Florida while Jerrico was on leave from Japan, fell in love at first sight, got married a year and a half later, and had three sons.

Life, they thought, would have certain assurances, a sense of security. They were young, but Jerrico was a veteran. There’s an unspoken rule with military service: He’d risked his life for the United States, and the U.S. government would now care for him and his family. Marines take care of their own, they say. “Semper fi.” Always faithful.

They thought.

Becca and Jerrico moved to the Laurel Bay housing base for Marines in Beaufort in 2013. At the time, their eldest son Jionni (or JJ, as his parents call him), had just turned 1. Becca was also pregnant with the couple’s second son. JJ played in the grass with other almost-toddlers, and the family often spent time at Laurel Bay’s playgrounds and parks.

JJ was a happy baby. But shortly after after the move to Laurel Bay, his sugar levels began spiking and dropping, spiking and dropping, Becca said.

One Saturday just after the family had moved to the housing community, JJ woke up, just like normal. But he soon grew tired, as if he “wasn’t entirely aware of his surroundings,” Becca remembered. He took a three-hour nap. He wouldn’t eat his lunch.

“It’s terrifying to see your kid on a day-to-day basis happy, having fun, playing, and then all of a sudden they kind of ... stop,” Becca said.

At first, Becca and Jerrico thought their son was diabetic. It wasn’t diabetes, however, and doctors failed to come up with a diagnosis. Almost nobody in Becca or Jerrico’s families had any record of autoimmune disorders, so it didn’t seem to have a genetic cause.

Then, JJ began developing constant ear infections. He got nosebleeds all the time, even in his sleep. Again, doctors were stumped.

Jerrico, too, confronted his own health problems. He’d rarely gotten headaches in the past, but while living on Laurel Bay, he was plagued with debilitating, daily migraines. Doctors gave him MRIs and CT scans, but they never found a definitive cause.

The Satryan family lived on Laurel Bay for about eight months. When they moved away to Georgia, Jerrico’s migraines and JJ’s sugar-level spasms stopped.

Well, Becca and Jerrico thought. That was that. It was strange, but it was over.

The family didn’t think much of those health problems after that. They had new health problems to deal with; specifically, with their second son, Sawyer. Early on, doctors diagnosed him with anemia, a condition in which a person’s body doesn’t have enough healthy red blood cells. This lack of red blood cells means that a person’s body tissues don’t get enough oxygen, which can lead to fatigue, irregular heartbeats and lightheadedness.

“He does bruise a lot,” Becca said. “He’ll have bruises on his spine from the car seat.”

Then, in January 2017, Becca started to notice a video being shared all over her Facebook feed.

The video was called “Laurel Bay Housing and Kids with Cancer.” In it, Amanda Whatley spoke about her daughter, Katie, who almost died from cancer. Whatley also spoke about storage tanks buried underneath the Laurel Bay neighborhood — storage tanks that had once been used to heat homes with heating oil, but that had been leaking.

“This is not, you know, conspiracy theory information, this is fact that the government has put out,” Whatley said in the video.

She was right, to an extent. This was no conspiracy theory — this was reality. Those storage tanks had been suspected of leaking benzene, a known carcinogen; and naphthalene, a possible carcinogen. But in large part, the Marine Corps failed to release information about the contamination, opting not to notify residents about the specifics of benzene and naphthalene.

At first, Becca avoided watching the video. She was naturally skeptical of outlandish claims, and Whatley’s assertion that Katie’s cancer may have been caused by the Marine Corps seemed too bizarre to be true. Sure, the military is making its own soldiers sick with contaminants. And congresspeople are all actually lizard people and Michael Jackson was secretly still alive — those scenarios seemed just as likely to her.

But the video kept popping up, especially in Facebook groups dedicated to Marine spouses. So, Becca finally caved. She watched it. Her curiosity piqued.

Shortly after, she read a news story about how the U.S. government was ordered to pay $2 billion to former residents of Lejeune Marine Corps Base in North Carolina. Residents of Camp Lejeune had been drinking contaminated water for decades and had been diagnosed with illnesses ranging from kidney cancer to Parkinson’s disease.

The Marine Corps learned about the contamination in the 1980s but did little to stop it.

“The same thing was happening here (at Laurel Bay),” Becca said. “It was mind-blowing!”

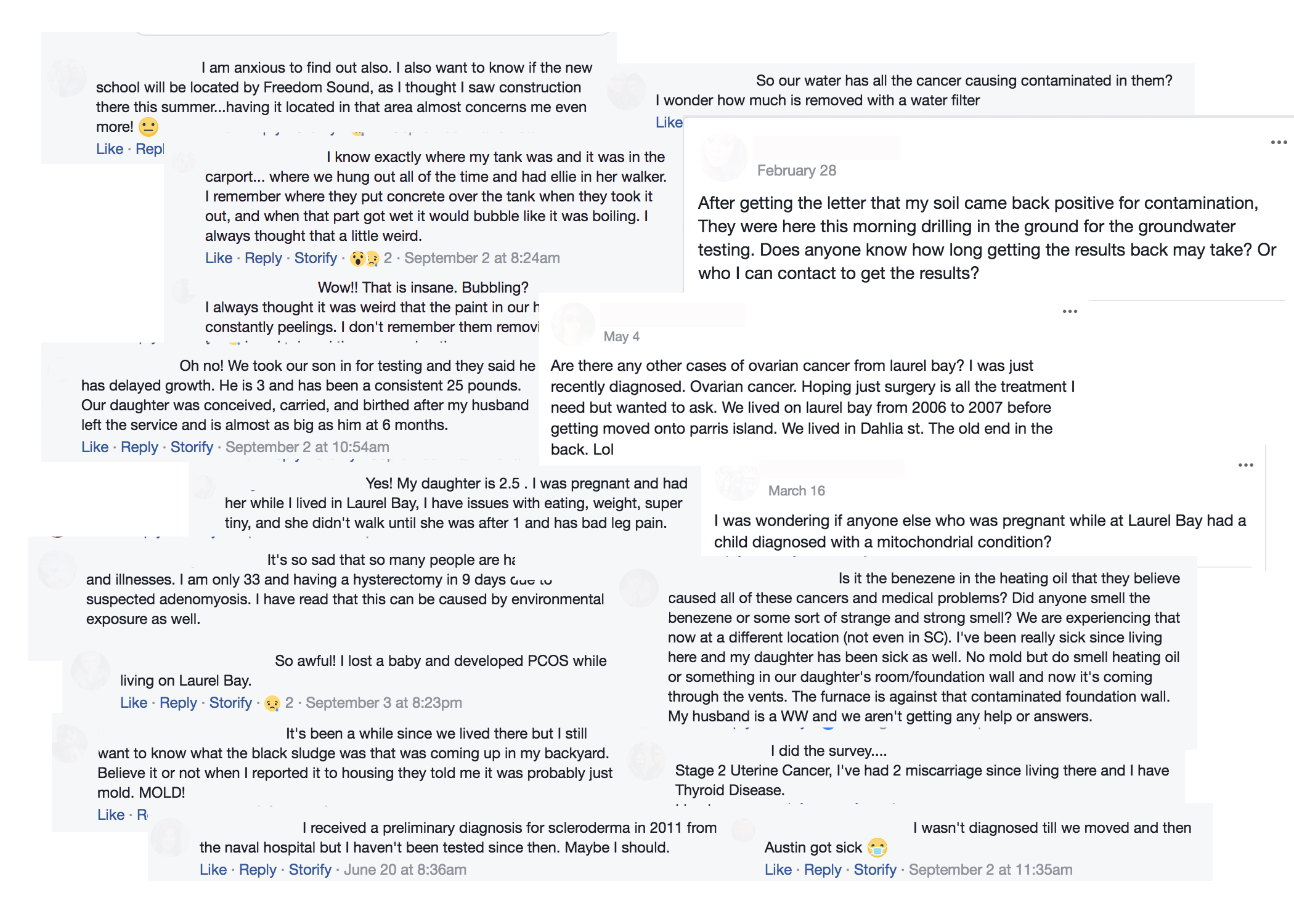

And then there was the last piece of the puzzle, the last argument that finally convinced Becca that something was very, very wrong: She found a Facebook group called “Concerned Military Family United by Pediatric Cancer BEAUFORT SC.”

Becca’s kids didn’t have cancer, thank goodness. But as she scrolled through, she saw that several parents mentioned other ailments affecting their children — anemia common among them.

Now, this caught Becca’s full attention.

Becca happened to be pregnant with Sawyer, her son with anemia, for the majority of the time that she’d lived on on Laurel Bay. She couldn’t help but wonder if there was a connection.

Becca soon became dedicated to the discussions on this Facebook group.

“Is it just me, or has anyone else lived here 2 years and Ms Whatley’s video was the first you’d heard of this?” wrote one Laurel Bay mother. “It was very irresponsible (for the Marine Corps) to have to leave it up to a hurt mother to have to share it with us.”

“Yeah never heard about this until now. Been in Beaufort since April 2012 and lived on base 2013-2014,” Becca wrote in response, echoing the other 46 comments on the thread.

That was true. During her time living at Laurel Bay, Becca had no inkling of leaking oil tanks. She couldn’t recall any notification letter in her mailbox. She didn’t remember any email sent to her or her husband. The Satryans, along with many other Laurel Bay families, were in the dark.

“Are you still having your children tested if it’s been almost 5 years since you’ve lived there? And they aren’t showing any symptoms?” another mother posted in the group.

“My middle son … bruises extremely easy and badly and is always covered in them for no apparent reason,” Becca wrote in January. “At the time they said we can watch it and see if he grows out of it because he’s all boy and he’s also really clumsy, but now I’m over here like” — here, she added three emojis of an alarmed face — “so we’re getting them tested even though it’s been 2.5 years.”

And that’s exactly what Becca and Jerrico did; they tested their children. Sawyer had anemia, but the doctor couldn’t tell his parents whether it had anything to do with Laurel Bay.

Another Laurel Bay resident posted in the group: “Has anyone had issues with SEVERE headaches coming at random times? …(T)hey come without any warning and no pain medicine has been able to help. It isn’t as extreme as a migraine, but it is like a blinding pain. I can’t do anything when they come except lay down. It’s brought me to tears before.”

Becca responded that this echoed her husband’s experience. “Unexplained,” she wrote. “They went away when we moved…”

Fast forward 11 months. It’s a warm November Sunday in Canton, Ga., and Becca and Jerrico have just moved into a new house. The young family’s new home is just north of Atlanta, but you wouldn’t know it without a map. It’s surrounded by acres of trees with golden and orange leaves.

Becca and Jerrico, now a veteran, tear the tape off boxes and unpack piles of toys. Cardboard boxes are stacked throughout the living room, and 4-year-old JJ and 3-year-old Sawyer run around their new house, pointing empty water guns at each other. Baby Anderson naps in a bedroom.

By all accounts, the Satryans are the picture of a happy young family.

A health study from the Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center concluded there was no “complete exposure pathway” for the contamination at Laurel Bay, and doctors hesitate to draw a direct connection between the contamination and illnesses.

But along with many other Marine families, the Satryans aren’t sure.

JJ stops whizzing around the living room when he sees his mother holding a photo of him from a few years ago.

“That’s me? That’s me?” he asks his mother. “I was a baby?”

“Yes, you were a baby,” Becca says.

In the photo, JJ and a friend sits in a small, kiddie pool in their backyard. It’s the type of plastic pool where the sides expand, and the pool itself is only six feet in diameter. Both children are wearing only diapers; JJ holds a red plastic shovel and grins at the camera.

It seems like an innocent enough photo. Regardless, it worries Becca.

Becca took the photo at the Laurel Bay Marine housing community in Beaufort in 2013. It was at this very time that officials were digging up storage tanks that had once been used to heat the homes with oil, but that had been leaking for decades. Benzene and naphthalene had been leaking into the ground, seeping through the soil and dirt. But Becca didn’t know, and she let JJ splash in the mud.

Becca and Jerrico remain frustrated that the Marine Corps never warned them.

Marine officials say there was no direct exposure to the contamination — Laurel Bay received its water through Beaufort-Jasper Water and Sewer Authority, and nobody was drinking the groundwater.

As she looked at the photo of JJ playing in that little plastic pool, Becca disagreed. Kids played in the dirt, she said. She worries they could have been exposed.

Now, Becca and Jerrico feel grateful. Sawyer’s anemia is manageable, and compared to children suffering from cancer, the family was lucky.

Nevertheless, that YouTube video and those Facebook discussions planted a seed of doubt in January. Could JJ’s illnesses return? Do JJ and Sawyer have any latent illnesses, those illnesses that show no signs or symptoms, and then appear with a vengeance years later?

Perhaps not. But perhaps so.

Once a seed is planted, it can germinate. And anxiety and uncertainty are optimal conditions for doubt.

Kasia Kovacs: 843-706-8139, @kasiakovacs

Next Story: Health scare in the schools

Coming Tuesday